Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Franklin Rosemont: Mods, Rockers and the Revolution

Mods, Rockers and The Revolution

Wobblies and other true revolutionaries are much less interested in the vague longings of college professors and Nobel prize-winners for a "better world" than in the day-to-day struggles of our fellow workers- not only the direct struggles against exploitation by the bosses, but the struggle to live some sort of decent life against all the obstacles presented by a society divided into classes. Thus it is essential that we concern ourselves not only with the job situation and economic questions but also with more "superstructural" anthropological factors: working class culture.

In this connection, the significance of rock'n'roll, and popular adolescent culture in general, has for too long been ignored. That rock'n'roll is one of the most important working class preoccupations (among the young, at least) is clearly evident. That it has been ignored by the "left" press is additional testimony to the isolation of the ‘socialist’ intellectuals from the class in whose name they so often enjoy speaking.

Certain unfortunate souls, including many of traditional "left" orientation, have attempted to deny that rock'n'roll is really a working class phenomenon, even suggesting that it is imposed (!) on working-class adolescents by Madison Avenue, etc., as a form of exploitation through cheap talent, record sales and juke-boxes. To them rock'n'roll is a sign only of the "decadence" of contemporary capitalist society. They can neither take it seriously as a form of music nor see in it anything other than a possible "reliever of tensions" which they feel might better be expressed in more constructive activity. Thus Marshall Stearns in The Story of Jazz, thoroughly puts down rock'n'roll as a form of music but claims that by offering "release" to anxious kids, it actually contributes to the decrease of juvenile delinquency. This uneasy, patronizing anti-rock'n'roll "theory" is, amusingly enough, shared by Stalinists, liberals, Presbyterians, conservatives and bourgeois sociologists.

We must have done, once and for all, with this kind of evasive excuse-mongering, and look at the situation as it really exists. Rock'n'roll must be recognized not only as a form of music (which, for its players and its listeners is clearly as "serious" as any other) but also as an important expression of adolescent preoccupations.

As music, rock'n'roll is certainly ‘primitive’ but this must not be assumed to mean that it is therefore inferior. No one is less able than musicologists and other prisoners of academic limitations to situate this problem in its proper context. For the importance of rock'n'roll lies not only in the music itself, but even more in the milieu which has grown up with it, characterized above all by delirious enthusiasm, a frenzy which is no stranger to tenderness, and which undoubtedly appears scandalous to the easily-outraged watchdogs of bourgeois morality.

Much could be said for the influence of rock'n'roll on the emergence of a new sensibility (intellectual as well as erotic and emotional). Much could be said, too, of its unconscious quality, which, with its roots in speed-up and automation (and thus in the class struggle) lends to its "subversive” aspect. For rock'n'roll is, more than anything else, a latent cultural expression of the age of automation. Indeed, a study of the psychoanalytical and anthropological implications of automation might well make rock'n'roll its point of departure. Witness the fact that almost all of the most popular rock'n'roll groups are from the most intensely industrialized and highly-automated cities: in the United States, Chicago and Detroit; in England, Liverpool, where one out of every fifteen "Liverpudlians" between the ages of 15 and 24 now belongs to a rock'n'roll group.

The best of the new groups - Martha and the Vandellas, Marvin Gaye, The Jewels, The Velvellettes, The Supremes, Mary Wells (all from Detroit), and The Kinks, The Zombies, Manfred Mann and, of course, The Beatles (all from England)- have brought to popular music a vitality, exuberance and rebelliousness which it has never seen before.

The Beatles are the most successful group in entertainment history. Their flippant replies to interviewers; their wild, raucous behavior; their riotous and insulting sense of humor remove them far beyond the pale of ‘respectable entertainers’. Their first movie, A Hard Day's Night, will remain one of the greatest cinematic delights of 1964, a lone cry of uninhibited freedom and irrationality in a cold desert of "seriousness" and pretentiousness.

The legendary quality, which can almost be called mythical necessity, of The Beatles, has not failed to attract the critical attention of some perceptive commentators. Consider this judgment from the pen of Jean Shepherd, who interviewed The Beades for Playboy magazine (February 1965):

‘In two years they had become a phenomenon that had somehow transcended stardom or even showbiz. They were mythical beings, inspiring a fanaticism bordering on religious ecstasy among millions all over the world. I began to have the uncomfortable feeling that all this fervor had nothing whatever to do with entertainment, or with talent, or even with The Beatles themselves. I began to feel that they were the catalyst of a sudden world madness that would have burst upon us whether they had come on the scene or not. If The Beatles had never existed, we would have had to invent them. They are not prodigious talents by any yardstick, but like hula-hoops and yo-yos, they are at the right place at the right time, and whatever it is that triggers the mass hysteria of fads has made them walking myths. Everywhere we went, people stared in open-mouthed astonishment that there were actually flesh-and-blood human beings who looked just like the Beatle dolls they had at home. It was as though Santa Claus had suddenly shown up at a Christmas Party’.

Another British group, The Rolling Stones, has risen to popularity more recently, bringing with them a more disquieting, more sinister, more violent attitude into the rock'n'roll arena.

It is in England where the adolescent revolt (of which rock'n'roll is only one constituent element) seems to have assumed its largest proportions. In England the kids are categorized into two "tendencies": Mods, fashionably (often bizarrely) dressed, and who are associated with motor-scooters; and the Rockers, who prefer black leather jackets, blue jeans, and motorcycles. In both cases the boys wear their hair long, considerably longer than in America, and (according to a New York Times writer from Britain) "the word in London and Liverpool is that male hair is going to get longer and longer." The girls' hair is usually straight and worn down to the middle of the back.

The hair itself deserves comment, particularly since hair is growing longer in the United States as well as in England and elsewhere in Europe. The social implications of hair fashion have been inadequately studied, if studied at all. Some psychologists and sociologists have confined themselves to brief, unexplained remarks on "sexual confusion”, "identity problems," and the like, which help very little. Others, it is true, have gotten a little closer to the heart of the matter. Thus the New York Times writer referred to above mentions that "sociologists, always a pessimistic lot, look on our jungled tresses and prophesy a future filled with indulgence and rebellion." For it is an undeniable fact that short male hair has always been a characteristic of submission to authority. The police, prisons, army, schools, and employers are all in agreement in insisting on short hair and regular haircuts. Also, crew-cuts are the symbol, almost, of Goldwater conservatism. Before making unfounded judgments on the "identity problems" of today's kids, one might consider the problems of a culture so obsessed with keeping male hair short.

The riots and brawls of the Mods and the Rockers have also called attention to another aspect of the youth revolt: that rock'n'roll represents the only mass protest music today- another reason why it deserves the sympathetic appreciation of revolutionaries. The most popular jazz has entcrcd the colleges and become respcctable. The most important developments in jazz during the last few years (Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Charles Mingus, Roland Kirk, et al.) are hardly known outside a small audience of connoisseurs. It is useless to point out that jazz is, musically, ten thousand times better than rock'n'roll; that's not the point. The audience for contemporary "classical" music is even more limited.

As for "folk" music and its derivatives (country-and-western, bluegrass, etc.) these have become the official expressions of today's college fraternities. (Real folk music is primarily of historical interest.) Those unhappy souls of the traditional "left" who try to pretend that the "folk revival" has some sort of revolutionary content rellect only their sentimentality and intellectual superficiality. I do not mean to imply that there's not much that is beautiful and important in the folk tradition, and certainly it deserves serious study. But it can no longer be assumed to have anything to do with the working class. At any rate, workingclass kids are bored by it. Like it or not, what today's workingclass kids are listening to is rock'n'roll.

The rise of the Mods and Rockers indicates to some degree a rise of young rebellion everywhere: the" new youth" of Tokyo, Berlin, Moscow, etc. Inevitably, this has provoked innumerable journalistic scare-stories about "new parent-teen crises" in Sunday supplements throughout the world. Such articles contribute nothing of importance to the understanding of the contemporary adolescent, though they do shed a little light on the problems and preoccupations of adults. Repressed adults, attempting to understand younger people, often merely project their own problems onto the kids.

Many parents, for instance, afraid of participating in uninhibited dancing, approach the question with the presuppositions that there is something wrong with this kind of dancing, and that it must be rooted in some deep emotional anxiety. I do not mean to say that rock'n'roll dances are expressions of "freedom" (the lack of physical contact berween dancing partners is especially problematical). But we cannot advance one step in our understanding of these problems if we begin by saying that the kids are wrong.

There can be no doubt that the present development of rock' n' roll, and the milieu of young workers in which it thrives, is more consciously rebellious than it has ever been before. To be revolutionary, of course, is to be more than rebellious, for a revolutionary viewpoint necessarily includes some sort of alternative. And popular adolescent culture is pregnant with revolutionary implications precisely because it proposes alternatives- however crude and undeveloped they may be- to the ignoble conditions now prevailing.

Songs like "Dancin' in the Streets" by Martha and the Vandellas and "Opportunity" by The Jewels show that the feeling for freedom and the refusal to submit to routinized, bureaucratic pressures, are not confined to small, isolated bands of conscious, politically "sophisticated" revolutionaries. Rather, they are the almost instinctive attitudes of most of our fellow workers. Presently these feelings are to a great extent repressed, and sublimated in bourgeois politics, television, baseball, and other diversions. It is our function as disrupters of the capitalist system, and as union organizers, to heighten consciousness of these feelings, to encourage rebellion, to do all we can to liberate the intrinsically revolutionary character of the working class. Rock'n'roll, which has already contributed to a freer attitude toward sex relations, can contribute to this liberation.

There is no use being overly romantic about all this. I do not, for example, think that adolescent hangouts and record hops will provide fruitful recruiting grounds for the One Big Union; at least, not right away.

And for my part, I vastly prefer the more raucous rhythm'n'blues - songs sung by ghetto Negro groups - to the lukewarm, diluted sounds promoted in teen-celebrity magazines and on American Bandstand.

But what revolutionaries must consider is that many younger workers - rock'n'rollers - are discontented with existing society, and are seeking and developing solutions of their own. If traditional revolutionary politics hasn't appealed to them, it's probably because these politics haven't been as "revolutionary" as their protagonists like to pretend.

We in the IWW are not tied to narrow theoretical traditions and immovable dogmas. We are rising today because we are free to seek new solutions and develop new tactics to meet new situations. If we are going to keep growing, we will have to turn more to the problems of younger workers. It might be noted that jobs most common to kids (stock work, filling-station work, store clerking, etc.) are almost completely unorganized, and offer us a splendid opportunity to channel the "youth revolt" into a consciously revolutionary movement.

In any case, we cannot go on assuming that the rock'n'rollers are a helpless, ignorant, reactionary mass; that their problems are not our problems; that they are somehow "irrelevant." We must recognize that the rock 'n 'rollers, too, despite the hesitations of" socialist" politicians, are our friends and fellow workers.

Sunday, April 26, 2009

Derek Jarman: gay clubbing in the 70s and 80s

Drugs are never far from the scene. After the hearts came Acid and quaaludes; then amyl, and something called Ecstasy. Someone always managed to roll a joint in a dark corner, and dance away into the small hours. It's certain that nobody who had taken the steps towards liberation hadn't used one if not all of them. The equation was inevitable, and part of initiation.

Now, from out of the blue comes the Antidote that has thrown all of this into confusion. AIDS. Everyone has an opinion. It casts a shadow, if even for a moment, across any encounter. Some have retired; others, with uncertain bravado, refuse to change. Some say it's from Haiti, or the darkest Amazon, and some say the disease has been endemic in North America for centuries, that the Puritans called it the Wrath of God. Others advance conspiracy theories, of mad Anita Bryant, secret viral laboratories and the CIA. All this is fuelled by the Media, who sell copy and make MONEY out of disaster. But whatever the cause and whatever the ultimate outcome the immediate effect has been to clear the bath-houses and visibly thin the boys of the night. In New York, particularly, they are starting to make polite conversation again - a change is as good as a rest. I decide I'm in the firing-line and make an adjustment - prepare myself for the worst - decide on decent caution rather than celibacy, and worry a little about my friends. Times change. I refuse to moralize, as some do, about the past. That plays too easily into the hands of those who wish to eradicate freedom, the jealous and the repressed who are always with us...

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Southall 1979

Punk band The Ruts were also involved in the People Unite collective and released Jah War, a song about the events on the People Unite record label. The lyrics include the lines: 'Hot heads came in uniform, Thunder and lightning in a violent form... Clarence Baker, No trouble maker, Said the truncheon came down, Knocked him to the ground, Said the blood on the streets that day'.

Punk band The Ruts were also involved in the People Unite collective and released Jah War, a song about the events on the People Unite record label. The lyrics include the lines: 'Hot heads came in uniform, Thunder and lightning in a violent form... Clarence Baker, No trouble maker, Said the truncheon came down, Knocked him to the ground, Said the blood on the streets that day'.See also:

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Dark Side of the Club

The Dark Side of the Club is an exhibition of clubbing and music photographs by Jamie Simonds now showing at the Gowlett pub in Peckham. There's some great shots, I particularly liked this one of a pirate radio operator (Kool FM I think) in action on an Aldgate rooftop.

The Dark Side of the Club is an exhibition of clubbing and music photographs by Jamie Simonds now showing at the Gowlett pub in Peckham. There's some great shots, I particularly liked this one of a pirate radio operator (Kool FM I think) in action on an Aldgate rooftop.

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Dancing Ledge

Are there many dancing places in the landscape? Obviously there are many places where people have danced in the open air, but what about places that actually have a dance-related name? Dancing Ledge in Dorset is one such place. Situated on the Isle of Purbeck a couple of miles south of Langton Matravers, it is a place created by quarrying. The removal of stone has created a flat surface next to the sea likened to a ballroom dancefloor, hence the name.

Are there many dancing places in the landscape? Obviously there are many places where people have danced in the open air, but what about places that actually have a dance-related name? Dancing Ledge in Dorset is one such place. Situated on the Isle of Purbeck a couple of miles south of Langton Matravers, it is a place created by quarrying. The removal of stone has created a flat surface next to the sea likened to a ballroom dancefloor, hence the name.Not sure how often people have actually danced there - it is a bit of a climb down the rocks - but in 'Old Swanage: Past and Present' (1910), W.M. Hardy mentions a picnic and dancing on the ledge with music from the Swanage Brass and Reed Band and 'a plentiful repast, consisting of lobster tea, salad and liquid refreshments'.

Derek Jarman was very fond of this place, calling his autobiography after it and filming parts of The Angelic Conversation and his punk movie Jubilee there. At the end of the latter, Queen Elizabeth I and John Dee walk at the Ledge, the queen declaring: 'All my heart rejoiceth at the roar of the surf on the shingles marvellous sweet music it is to my ears - what joy there is in the embrace of water and earth'.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Songs about dancing (6): Out on the Floor

From 1965, this Northern Soul classic by Dobie Gray has been an anthem for many years for some of the most committed dancers ever to have graced a dancefloor. There is something incredibly joyous about this song, to actually be out on the floor while listening/dancing to this record is such a buzz, a perfect beautiful loop - listening to 'on the floor' a joyous song about dancing while dancing joyously on the floor to the song...

'I am on the floor tonight, I feel like singin'/ The beat is running right and guitars are ringin'/ I'm really on tonight and everything swingin' / The room is packed out tight, light at the door/ I Get My Kicks Out On The Floor' (full lyrics at the excellent awopbopaloobopalopbamboom (from where I also sourced the scan of the label).

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

Hillsborough 1989

Hillsborough has now become yet another placename to add to those that make up the by-now voluminous gazeteer of wasted human lives. Already there has been talk of "learning the lessons of Hillsborough"; but if the lessons of Bradford, Heysel, Manchester Airport and the Herald of Free Enterprise had been even half absorbed, this most cruel visitation might have been avoided.

What all these have in common is that they arose from the processing of people through time or space for the sake of experiences provided by the entertainment, holiday and sports industries; as such, they touch upon one of the central purposes of the economy in its most benign guise - that of leisure society. This, it turns out, is dedicated to the necessity of making as much money out of people as possible, in this instance, by making them pay - some, alas, with their lives for the privilege of standing for two hours in what are nothing more than overcrowded cages.

Because these experiences are associated with pleasure, it is easy to disregard the dangers, whether these are the use of unsuitable material in the manufacture of aircraft seats, insecure and overloaded ferry boats, or football grounds that prove to be deathtraps. It is only when things go wrong that some deep insight is granted us into the true value placed on human life by the purveyors of entertainment, escape and fun to the people.

"We were like animals in a zoo," said one man afterwards. It was a zoo in which the watchers were primarily electronic: the cameras of the media, the police videos and computers, represent a vast investment in the paraphernalia of surveillance, which could monitor every anguished moment, but do absolutely nothing to help. What a contrast this prodigious outlay of money presents with the absence of life-saving equipment. The doctors present testified that there were no defibrillators, and that the oxygen tents were without oxygen; but the presence of all the media hardware ensured that the spectacle of football was swiftly transformed into a spectacle of a quite different genre.

The carnage – how sad that the hyperbole of football writing becomes hideously appropriate – raises intently political issues. Those who insist upon referring to the incident as though it were an Act of God, a sort of natural tragedy, betray only their interest in concealment. The very public display of their humanitarian concern merely masks its absence in the more fundamental matter of preventing the gratuitous squandering of young lives.

Football is perhaps the only remaining experience in our social life where passion - and partisan passion at that - is engaged. Nothing could be further removed from the other characteristic crowd scenes in our society: the people shuffling through the shopping malls, for instance, are self-policing, introspectively concerned as they are upon the relationship between individual desire, money and the prize to be purchased; remote too from pop concerts, where the shared focus of cathartic emotion is funnelled on to a single person, and its expression is without conflict.

But football continues to reach something which neither of these possesses - the passion of locality, and of places once associated with something more than football teams. That Liverpool should have been connected twice with such unbearable events is perhaps not entirely by chance. For the great maritime city, with its decayed function rooted in an archaic Imperial and industrial past, sport now has to bear a freight of symbolism that it can scarcely contain.

The energies of partisan, mainly working-class male crowds remain, as they always have been, the object of great anxiety and suspicion to their betters. These energies are perceived as perhaps the last vestiges of the turbulence of the mob - unruly, defiant and unpredictable - in a society where all other public passions have been tamed.

The forces released by football provide a glimpse of collective power that has been successfully neutralised in the rich Western societies; a suggestion that such passion could possibly be harnessed to social and political endeavour rather than sublimated in sporting conflicts.

Apart from the sight of the inert young bodies stretched out in the sunlight, perhaps the most chilling images were those of the anguished faces pressed against wire fences. They looked as if they had been taken from the iconography of repression of authoritarian states, and they evoke something quite other than the idea of sport. They bore the tormented expression of those in prison camps; indeed, many spoke of "the terracing that had become a prison", the inevitability of disaster within those reinforced enclosures, where the grisly facts of the quantity of pressure they. were calculated to withstand was conveyed with scientific precision.

We can only guess at what unwanted and redundant human powers are being controlled in the use of all this apparatus of containment; what frustrated visions and cancelled dreams are being policed, what doomed alternative use of these energies is being fenced in, sifted through the mechanistic click of the turnstiles. What an irony is the Government's obsession with identity cards in this context, when it is precisely a sense of identity that so many are trying to reclaim in these conflicts between geographic entities that have become, physically, interchangeable. For what now differentiates Sheffield from Nottingham, Manchester from Liverpool, Bradford from Leeds, with their homogeneous housing estates, the sameness of their shopping centres, the identical service sector economy?

There remains also an old class prejudice in the treatment of those who must be systematically humiliated in the pursuit of their afternoon's pleasure. "We are treated like animals," some said afterwards; and in their words is an echo of how Government ministers had described them at the time of earlier disasters. The very idea of "fans" is a humbling social role, a diminishing and partial account of human beings.

Indeed, there could be no greater gulf than that created by the exaggerated adulation that the stars and heroes receive - the inflated transfer fees, the publicity, the column inches and admiring TV interviews - and the abasement and inferiorising of the fans, punters or consumers. The players are mythicised, whisked upwards into an empyrean of fame and celebrity, in which everything they do or say is reported, no matter how trivial; in the process they become remote from their votaries and followers, who are kept in their place as effectively as they once might have been through the mysteries of breeding or station. Part of the process of erecting the infamous steel barriers is connected with enforcing this separation: the pitch is inviolate, the fans must remain content with the wall poster, the autograph, the fantasy.

Already, the aftermath of these tragic disasters has taken on the aspect of a known ritual: the Prime Minister arrives, prayers are offered up, shrines are set up at the scene of the accident, and a fund is opened. It means that these inadmissable horrors have become part and parcel of our social life; they have become familiar. Once again, the real lessons are likely to be that the public enquiry will be a vast exercise in concealment of the true relationship of these unnecessary tragedies to the necessities of what are no longer amiable Saturday afternoon pastimes but are part of a remorseless machine for making money; how fitting that the advertising hoardings had to serve in place of absent stretchers.

More: see the Hillsborough Justice Campaign; there's also a couple of good articles by Merrick at Head Heritage, one summarising the Hillsborough events and the other comparing the policing of football fans with the recent G20 protests.

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Blue Murder

Liddle Towers was a 39 year old electrician and amateur boxer from Gateshead who was arrested outside the Key Club in Birtley (Northumberland) in January 1976. He told people that the police 'gave us a bloody good kicking outside the Key Club, but that was nowt to what I got when I got inside'. A few weeks after being released from custody he died of his injuries. An inquest into his death recorded the notorious verdict of 'Justifiable Homicide'.

Liddle Towers was a 39 year old electrician and amateur boxer from Gateshead who was arrested outside the Key Club in Birtley (Northumberland) in January 1976. He told people that the police 'gave us a bloody good kicking outside the Key Club, but that was nowt to what I got when I got inside'. A few weeks after being released from custody he died of his injuries. An inquest into his death recorded the notorious verdict of 'Justifiable Homicide'.The Upstarts sang: 'Why did he die, or did they lie? I think he's dead, so a doctor said / He was beaten black, He was beaten blue / But don't be alarmed, it was the right thing to do / The police have the power, Police have the right / To kill a man to take away his life / Drunk and disorderly was his crime / I think at worst he should be doing time / But he's dead / He was drunk and disorderly and now he's dead' .

Sex Pistols producer Dave Goodman released a record called 'Justifiable Homicide' on the same subject in 1978, apparently with Paul Cook and Steve Jones from the Pistols playing on the track.

Sex Pistols producer Dave Goodman released a record called 'Justifiable Homicide' on the same subject in 1978, apparently with Paul Cook and Steve Jones from the Pistols playing on the track.The Tom Robinson Band dedicated their 1979 album, TRB Two to Mrs. Mary Towers, the mother of Liddle Towers. The song Blue Murder on this album goes: 'Well they kicked him far and they kicked him wide / He was kicked outdoors, he was kicked inside / Kicked in the front and the back and the side / It really was a hell of a fight... / He screamed blue murder in the cell that night / But he must have been wrong cos they all deny it / Gateshead station - police and quiet/ Liddley-die... / Lie lie lie diddley lie /Die die die Liddley die'.

The Death Song for Alfred Linnell 1887

Liddle Towers was not the first or the last person to die at the hands of the police to be commemorated in this way. Way back in 1887, Alfred Linnell was killed in clashes with police during the Bloody Sunday demonstration n London's Trafalgar Square (pictured below). William Morris helped carry his coffin, and wrote the Death Song to raise money for Linnell's family: 'What cometh here from west to east awending? / And who are these, the marchers stern and slow? / We bear the message that the rich are sending / Aback to those who bade them wake and know / Not one, not one, nor thousands must they slay, / But one and all if they would dusk the day'.

Kevin Gately 1974

In 1974 Kevin Gately, a young student, was killed in Red Lion Square, London, during an anti-National Front demonstration. Gately is mentioned in a song called Spirit of Cable Street by People's Liberation Music, featuring Cornelius Cardew and recorded in 1976: 'Now at Red Lion Square the people fought with bare hands / Like their parents did down at Cable Street / Keep alive the fighting spirit of Kevin Gately / Brave anti-fascist fighter. / Unite in the spirit of Cable Street'.

Blair Peach 1979

30 years ago this month, on 23 April 1979, socialist teacher Blair Peach died at the hands of the police Special Patrol Group during anti-National Front protests in Southall, West London. Linton Kwesi Johnson recorded a track 'Reggae fi Peach' on his 1980 album Bass Culture (there is a dub version of this track on the album LKJ in Dub; Basque band Negu Gorriak have also recorded a version as Reggae Peachentzat).

The lyrics include the lines 'Everywhere you go it's deh talk of the day /Everywhere you go, you hear people say / ... ah deh S.P.G. dem a MURDER-AH, MURDER-AH / we can't let dem get, no furder-ah / because dem kill Blair Peach, deh teacha dem kill Blair Peach dem dogs 'n bleeders / Blair Peach was an ordinary man / Blair Peach him took a simple stand / 'gainst deh fascists and dem wicked plan / so they beat him till him life was gone'.

There is also a 1979 song by Mike Carver called Murder of Blair Peach, while the track Justice by The Pop Group mentions both Peach and Gately: 'Who killed Blair Peach? / Political prisoners caught at Southall / And tried by kangaroo courts / A man had to have his balls removed/ After being kicked by the S.P.G. / It doesn't look like justice to me... / Who guards the guards / Who polices the police / What happened at Red Lion Square / Who killed Kevin Gately'.

Colin Roach 1983

Colin Roach died from gunshot wounds at Stoke Newington Police Station in 1983, with many people reluctant to believe the police version that he had shot himself. Benjamin Zephaniah wrote a poem which starts ' Who killed Colin Roach? A lot of people want to know /Who killed Colin Roach? dem better tell de people now, /what we seek is the truth, youth must now defend de youth /Who killed Colin Roach? tell de people now'.

Sinéad O'Connor's Black Boys on Mopeds also refers to the death (without naming Roach) - the sleeve of her album 'I do not want what I can't have' includes a picture of Colin and thanks to to the Roach family. The song includes the line: 'England's not the mythical land of Madame George and roses. It's the home of police who kill Black boys on mopeds'.

Wednesday, April 08, 2009

Party on Beef Millionaire's Estate

This is kind of 'spatial poaching' isn't it? Instead of sneaking on to the estates of wealthy landowners to poach deer, people temporarily appropriate space for a party. Those who know the history of Reclaim the Streets will appreciate the irony of the location for this particular party.

Monday, April 06, 2009

Drugs Raid at the Peace Cafe 1962

'On 12 March 1962 The Times carried the headline ‘Drug Charges After Raid On Café’ above an article that mentioned Green among others, then on 26 March 1962 the same paper followed this up with ‘C.N.D. Supporters Given Drugs’, concluding on 26 April with a news story entirely devoted to Phil Green entitled ‘Youth’s Beard A Part Of Façade’. Philip John Green then aged twenty was one of ten men and women arrested for their involvement with a ‘drug ring’ centred on The Peace Café in Fulham Road, Chelsea. At the time Green worked at this establishment as a chef. He pleaded guilty to possession of Indian hemp and twenty grains of opium, as well as ‘hubble bubble pipes’ used for opium smoking'.

The Peace Cafe was described in court as a supposed 'local headquarters of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament' that was actually a place where drugs were 'administered to young people who were supporters of that campaign and congregated there' (Times 26.3.1962). The Magistrate referred to it as 'an absolute den of iniquity and debauchery' when sentencing the manager, Kenneth Browning to 2 month's imprisonment 'for permitting the cafe to be used for smoking opium'. Browning told the court that he had been a supporter of the Committee of 100, the direct action wing of the peace movement (Times, 4 April 1962).

I haven't found out anything more about this place, except that a Peace Cafe was opened in the 1960s in Fulham by Rachel Pinney, a member of the Direct Action Committee against Nuclear War. I assume this was the same cafe, one of those places where currents from the beatnik, drugs and radical political scenes intersected several years before the 'counter culture' became a media phenomenon.

If you know any more about the Peace Cafe, or any other interesting clubs, bars and coffee houses from that time please leave a comment.

(see also The Gyre and Gimble)

Friday, April 03, 2009

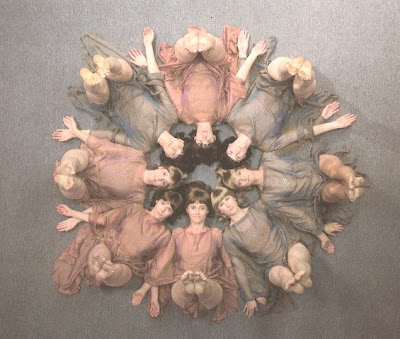

Oism

The centrepiece of the exhibition was a film where 'the artist orchestrates a symphony of gestures to create a dream like sequence. Here Shaw merges the extravagancy of Busby Berkeley’s films with the esoteric dances instigated by spiritual leaders such as G.I Gurdjieff'. It was a perfect recreation of how you might imagine such a film from the mid-1970s, a group of women in diaphanous tabards floating around a Banyan tree and lying on the floor doing dance moves as if from a synchronised swimming routine (or indeed a Berkeley movie). The styling was uncanny, with the women dancers embodying a very specific period model of beauty -not just in terms of the haircuts (think Joanna Lumley's Purdey cut) but in terms of being older than the current media/marketing ideal.

Wednesday, April 01, 2009

California: raves not 'consistent with the values of our community'

Thursday, March 26, 2009

Tina Modotti

In 1913, aged 16, she moved to San Francisco where she became an actress. She had a starring role in a Hollywood silent movie, The Tiger's Coat (1920), playing a Mexican servant who ended up heading a dance troupe.

In 1913, aged 16, she moved to San Francisco where she became an actress. She had a starring role in a Hollywood silent movie, The Tiger's Coat (1920), playing a Mexican servant who ended up heading a dance troupe.Leaving aside this terrible episode (in which the extent of her complicity is a bone of contention), I think we can still appreciate her photography and wonder what it would have been like to have gone to one of her legendary parties. Just after the First World War she lived with her lover Ricardo Gomez Robelo in LA:

Living in Mexico City with Edward Weston, Modetti was once again at the centre of bohemian social life:

Virtually every well-known writer and artist in Mexico participated. Mexican-born, Texas-educated journalist Anita Brenner described how 'workers in paints drank tea and played the phonograph with union and non-union technical labour-scribes, musicians, architects, doctors, archaeologists, cabinet-ministers, generals, stenographers, deputies, and occasional sombreroed peasants."

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

More Silent Raves

Not so silent in Milton Keynes was a party in a Church Hall. The 18 year old organiser received a police caution for fraud after booking the hall for a family '50th birthday party' and then inviting hundreds of people via Facebook who apparently left the 'area strewn with broken glass, cans, beer bottles and glow sticks'.

Monday, March 23, 2009

Miners Strike: (2) Kent; (3) Dick Gaughan

When the Miners Strike started in 1984 I was living in Whitstable in Kent, very close to the small Kent coalfield. The Kent mining villages in the 1980s were radically distinct from the surrounding area. In the middle of the 'garden of England' the three pits of Snowdown, Tilmanstone and Betteshanger were more or less the only major industry, employing two thousand miners, many of them living in the villages of Aylesham, Elvington and Mill Hill on the edge of Deal. A fourth Kent pit, Chislett, had been closed in 1968.

Betteshanger in particular had a long history of militancy. During the Second World War, three union officials were imprisoned and over 1000 men were prosecuted after going on strike. In 1961 miners occupied the pit for 6 days in a stay-down strike in a successful protest against redundancies - 'an old record player was sent down the pit, and each of the teams organised a show of songs and comedy acts' (Pitt). In the 1972 strike, Kent miners had travelled around the country as 'flying pickets' .

Map of the Kent coalfield (from Pitt)

My first introduction to the mines was during my pre-strike time in the Socialist Workers Party when the worst task for a drinking and smoking student was a paper sale at the pit gates early in the morning as the miners were changing shifts. We never seemed to sell more than 1 or 2 - there were a few vaguely sympathetic miners, but nobody wanted to talk politics a couple of hours the wrong side of dawn. Most just walked by no doubt wondering quite rightly why anyone would want to get out of bed that early unless they had to. Soon I too was crying off the early shift, and indeed the whole trotskyist project, but that's another story.

When the strike started, me and some friends at our college (University of Kent at Canterbury) took the initiative to set up a Miners Support Group. The aim was practical solidarity - we collected money, organised transport to demonstrations and pickets and generally encouraged support for the strike. There was plenty of support to be tapped into, even though for most people this never went beyond putting some money in a bucket and wearing a 'coal not dole' sticker. As the radical historian Raphael Samuel perceptively argued at the end of the strike: 'In retrospective it can be seen that support for the strike, though fervently expressed, was also precarious; that it was predicated on the miners' weakness rather than their strength; and that it owed more to a humanitarian spirit of Good Works, than, in any classical trade union sense, solidarity, and it is perhaps indicative of this that the local organisation of aid took the form of Miners Support Groups rather than, as in 1926 - an analogy fruitlessly invoked - Councils of Action. The support was heartfelt and generous, but with the important exception of the seamen, the railwaymen and the Fleet Street printers, it did not involve stoppages of work'.

Coal Not Dole - slogan in Whitstable, Kent (by the Labour Club)

Coal Not Dole - slogan in Whitstable, Kent (by the Labour Club)

The strike polarised society with passionate support on the one hand and equally virulent opposition on the other. We encountered some of the latter in Kent too, from the college official who tried to stop us collecting to our landlord in Whitstable who tried to get us to take down posters from our window.

Kent NUM leaflet from May 1984 [click on pictures to enlarge] - 'Our fight is a fight for everyone' - the language of this leaflet is very much in line with the Communist Party of Great Britain politics of Kent NUM leaders Jack Collins and Malcolm Pitt, combining calls for solidarity with appeals to nationalist sentiment (e.g. 'The Coal Mining Industry of Britain belongs the whole nation')

When the strike started, the Kent miners unanimously joined in. In Nottinghamshire many miners continued to work, and strikers from Kent travelled up to the Midlands to join their comrades from Yorkshire in picketing the working mines. The police mounted a massive operation to prevent the Kent miners from moving around the country. 'On Sunday March 18th, police officers from the Kent constabulary attempted to stop anyone who appeared to be a miner or who was going north to aid the miners strike from crossing the Thames through the Dartford Tunnel'. Strikers were threatened with arrest for trying to leave Kent, even though the police had no legal powers to stop them (State of Siege).

Malcolm Pitt , President of Kent National Union of Mineworkers, was jailed for 18 days for defying bail conditions which prohibited from going anywhere near a picket line. I took part in pickets of Canterbury Prison, where he was being held in May 1984.

Later in the strike, some Kent miners did begin to go back to work and the strikers mounted pickets of the Kent pits. The Miners Support Group joined the pickets, and the canteen in the miners welfare club had to get used to the vegetarian demands of student radicals!

The Kent miners were the last return to work in March 1985, staying out longer than the rest of the country in an attempt to win the reinstatement of miners sacked during the strike. Within five years all three of the remaining Kent mines had been closed for good, with the loss of 2000 jobs (Betteshanger was the last to go in 1989)

References: Malcolm Pitt, The World on Our Back: the Kent Miners and the 1972 Strike (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1979); ; Raphael Samuel, Barbara Bloomfield and Guy Boanas (eds.), The Enemy Within:Pit villages and the Miners Strike of 1984-5 (London: Routledge, 1986); Jim Coulter, Susan Miller and Martin Walker, State of Siege: Miners Strike 1984- Politics and Policing in the Coal Fields (London: Canary Press, 1984). There's some interesting material on the strike in Kent here

Dick Gaughan

The folksinger Dick Gaughan was a tireless supporter of the Miners Strike, performing at benefit gigs all over the UK. Immediately after the strike he wrote a song about it entitled The Ballad of 84, first performed at a benefit for sacked miners at Woodburn Miners Welfare Club in Dalkeith, Midlothian in '85.

Gaughan's song recalls the strikers who died, as well mentioning Malcolm Pitt and others who were imprisoned:

Let's pause here to remember the men who gave their lives / Joe Green and David Jones were killed in fighting for their rights / But their courage and their sacrifice we never will forget / And we won't forget the reason, too, they met an early death / For the strikebreakers in uniforms were many thousand strong / And any picket who was in the way was battered to the ground / With police vans driving into them and truncheons on the head/ It's just a bloody miracle that hundreds more aren't dead... And Malcolm Pitt and Davy Hamilton and the rest of them as well / Who were torn from home and family and locked in prison cells'.

You can listen to the song here.

I will be doing some more posts about the miners strike, if you can recommend any songs (or better still point me in the direction of MP3s) let me know. Particularly keen to get hold of Chumbawamba's Common Ground and Fitzwilliam - my tapes long lost - and The Enemy Within track (done by Adrian Sherwood).

Friday, March 20, 2009

Sapeurs of Bakongo

The book blurb notes that 'In 1922, G. A. Matsoua was the first-ever Congolese to return from Paris fully clad as an authentic French gentleman, which caused great uproar and much admiration amongst his fellow countrymen. He was the first Grand Sapeur. The Sapeurs today belong to 'Le SAPE' (Societe des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Elegantes) - one of the world's most exclusive clubs. Members have their own code of honour, codes of professional conduct and strict notions of morality. It is a world within a world within a city. Respected and admired in their communities, today's sapeurs see themselves as artists. Each one has his own repertoire of gestures that distinguishes him from the others'.

More Sapeur photos by Hector Mediavilla (who took the picture above here).

(note to self - must get round to doing that post on proletarian dandyism...)

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Flash Mob Simulacrum Continued

In the comments to Stewart's post, someone mentions Baudrillard and his notion of the Simulacrum. I must admit, though not an uncritical admirer, my first thought when I read that T-Mobile had created a simulation of a flash mob (in itself arguably a simulation of a Reclaim the Streets party), and that subsequently thousands of people had created a real flashmob partly as a simulation of this simulation - thus rendering the notion of what was 'real' at least problematic - my first thought was 'Blimey, Baudrillard eat your heart out'. Unfortunately Baudrillard is no longer around to spin a few moments of flashmobbing into a pithy if incomprehensible epigram.

Wednesday, March 18, 2009

Moving Gallery - The Mysterium

The inspriation was Alexander Scriabin's never realized plan for his Mysterium, a work that called for a cast of 1000 musicians and dancers to realize his vision where: 'There will not be a single spectator. All will be participants. The work requires special people, special artists and a completely new culture. The cast of performers includes an orchestra, a large mixed choir, an instrument with visual effects, dancers, a procession, incense, and rhythmic textural articulation. The cathedral in which it will take place will not be of one single type of stone but will continually change with the atmosphere and motion of the Mysterium. This will be done with the aid of mists and lights, which will modify the architectural contours."

For this event, every corner of the building seemed to have been turned into a space for performance and installations, with corridors, corners and rooms full of dancers and musicians, through which the audience wandered between and within waves of movement and sound.

We particularly enjoyed Night Chant, a beautiful piano performance by GéNIA (picutre below), inspired by Yeibichai (Night Chant), a Navajo ritual. The Aviary, a bird themed performance by the group The Conference of Birds, also felt quite shamanic with dancer Helka Kaski moving as if she was channelling a bird.

The Practice Corridor, a homage to Rebecca Horn's Concert for Anarchy, featured eruptions of piano noise with dancers and pianists moving around the corridor:

The Practice Corridor, a homage to Rebecca Horn's Concert for Anarchy, featured eruptions of piano noise with dancers and pianists moving around the corridor: The baroque buildings, designed by Christopher Wren, used to be part of the Royal Naval College in Greenwich. Trinity College of Music, which occupies them now, remains tied to Royal patronage but nevertheless it was pleasing to see a former hub of the Empire and military transformed into a festive space. And indeed for some of the ex-colonial subjects to temporarily take over some of the space - Samvaada was a musical collaboration between the Bhavan Institute for Indian Arts and some Trinity music students:

The baroque buildings, designed by Christopher Wren, used to be part of the Royal Naval College in Greenwich. Trinity College of Music, which occupies them now, remains tied to Royal patronage but nevertheless it was pleasing to see a former hub of the Empire and military transformed into a festive space. And indeed for some of the ex-colonial subjects to temporarily take over some of the space - Samvaada was a musical collaboration between the Bhavan Institute for Indian Arts and some Trinity music students: The final piece was Snowscape, outside in the courtyard, and beginning with a procession of a dancer wrapped in lights.

The final piece was Snowscape, outside in the courtyard, and beginning with a procession of a dancer wrapped in lights. Watching contemporary dance can sometimes feel like hard work, and we weren't sure whether we were going to enjoy four hours of performance. As it happened we ended up only being able to take in a fraction of the events and wished it had gone on longer. In fact it would have been interesting if it had gone on all night, and perhaps begun to get a little messier with the boundaries between audience and performers maybe blurring a bit more.

Watching contemporary dance can sometimes feel like hard work, and we weren't sure whether we were going to enjoy four hours of performance. As it happened we ended up only being able to take in a fraction of the events and wished it had gone on longer. In fact it would have been interesting if it had gone on all night, and perhaps begun to get a little messier with the boundaries between audience and performers maybe blurring a bit more.

Sunday, March 15, 2009

Miners Strike (1): Here We Go

The focus of the strike was the threat of pit closures, but everybody involved knew that there was much more at stake than simply jobs in the mining industry (important as that was). Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government was clearly determined not just to win the strike but to decisively break the most powerful section of the working class. Ten years before (in 1974) the previous Tory government had after all been forced to resign after a miners strike, and another strike in 1972 had led to power cuts.

This time round the state had made elaborate preparations, stockpiling coal and putting in place a massive police operation. As a result, the direct economic impact of the strike was minimised - power stations and other industries were not closed down, a major factor in the strike's eventual defeat a year later. The strike did though have a huge impact across society, and it has now assumed a kind of depoliticized iconic status. Witness the ongoing success of the film/musical Billy Elliot, the story of a young boy learning to dance against the backdrop of the strike. Witness too a recent advert for Hovis bread in which images of the strike feature in a parade of images of Northern authenticity that the little brown loaf has borne witness too!

I am not even going to attempt an overall analysis of a year of hope, violence, solidarity, betrayal and ultimately defeat. But I am planning a series of posts setting down some of my memories and reflections, including some of the musical aspects of the strike.

Here We Go

Several songs were written about the Miners Strike, and many more performed at the countless benefit gigs up and down the country. But if there's one piece of singing that reminds more than any other of the strike it's the chant 'Here We Go', heard on demonstrations and picket lines, and sungalong to in bars and parties. For instance, Bob Hume recalls that at Hatfield Main Miners Welfare club in Yorkshire 'We brought the New Year in [1985] with a disco/buffet... knees up, for all our kitchen staff, pickets and visiting friends, the night and early morning came with rousing 'Here We Goes', the Red Flag and Never Walk Alone'.

Here We Go is a football chant (in the US as well as UK) sung to the tune of Sousa's Stars and Stripes Forever. Banner Theatre recorded a cassette based on the strike called "Here We Go" in 1985. The cartoon below from the time of the strike shows Thatcher & Co. singing the song as the car of 'British Capitalism' heads towards a crash.

(The Bob Hume quote comes from 'A Year of Our Lives: Hatfield Main, a colliery community in the great coal strike of 1984/5', Hooligan Press, 1986)

Friday, March 13, 2009

Dancing and Xhosa Resistance

A close association of millennialist prophecy and warfare against intruders occurred in South Africa during the unsettled period of European conquest in the first half of the nineteenth century. European misconceptions of the tribal system of the Bantu and, even more, the misapprehension of the missionaries concerning native religion, were important factors in the wars between the Xhosa and the British forces in the Cape in the carly nineteenth century.

... Ndlambe [leader of many of the Xhosa groups], who had been a persistent enemy of the British... was pushed over the Fish River by British forces in the Fourth Kaffir War in 1812. A prophet, Makanna, arose as Ndlambe's adviser, and he persuaded Ndlambe's following, and the warriors of the Gcaleka, that with his aid the bullets of the English would turn to water, and the English themselves would be pushed into the sea. The numbers involved on the two sides were so utterly disproportionate that, once bullets were neutralized, such a result appeared a certainty. He would release lightning against them, and ensure victory for Ndlambe's warriors...

He taught that he was the emissary of Thlanga, creator of the Xhosa, who would raise ancestor spirits to assist them in battle. The god of black men, Dalidipu, was greater than the white god, Tixo, and Dalidipu's wife was a raingiver, while his son was Tayhi, the Xhosa name for Christ. Dalidipu sanctioned the Xhosa way of life, including the customs of polygamy and brideprice, which the missionaries said were sins. Makanna taught that black men had no sins except witchcraft, since adultery and fornication were not sins: on the other hand, the white men were, on their own admissions full of sins. Dalidipu would punish Tixo, and the white men would be destroyed. If the Xhosa danced, they could bring back the ancestors, who would come armed and with herds of cattle.

The British were allied with Gaika [leader of another group of Xhosa], who was the first object of attack by Ndlambe and Makanna. His defeat led the British into the Fifth Kaffir War of 1818-19, but their first success against Ndlambe's men beyond the Fish River did not prevent further hostilities between Gaika and Ndlambe, and Makanna's army crossed the Fish River singing that they would chase the white men from the earth. On 23 April 1819 ten thousand warriors, led by Ndlambe's son, Dushane, and Makanna attacked Grahamstown, which they failed to take and where they suffered heavy losses. This failure did not, however, bring about Makanna's downfall, and the war continued with the British driving the Xhosa back as far as the Kei River. In August Makanna gave himself up because his people were starving, and, so he declared, to see whether this would restore the country to peace. He was drowned some months later in attempting to escape, after his fellow prisoners on Robbell Island had overwhelmed the guard and made a bid for the mainland. That he was dead was not believed by the Xhosa, who for years expected his return to help them.

Source: Bryan Wilson, Magic and the Millennium (London: Heinemann, 1973).