Wednesday, October 08, 2025

Handsworth Revolution - yes please

Wednesday, August 06, 2025

'Youths fight police kill-joys' (1977) - cops at Bob Marley and Delroy Wilson gigs

Saturday, March 01, 2025

Denzil Forrester in Lives Less Ordinary

In an ArtCornwall interview Forrester has recalled this time in the 1980s:

'I grew up in Stoke Newington and Hackney, and a lot of the paintings...are to do with the nightclubs in the Dalston area, mainly Jah Shaka sound system; mainly the dub reggae sound systems in the early days... I used to go to the London nightclubs and make drawings to the length of a record, which is about 3 or 4 minutes.

So I'll have A1 paper, it's dark, and I can't really see what I'm doing, so I'm going for the movement, the action, the expression of the people. I'll make the drawings, and take them to the studio and use them for making the big paintings in the studio... London was a very active, vibrant, colourful place then. It was cheaper and freer to live there then too. You could squat a house. So I was in a squat for about 5 to 6 years in Clissold Road. It was easier because an artist could have lots of space. And there was an energy there. Particularly the dub nightclubs. Jah Shaka, the Rastafarians, basically they'd dress up, they'd dance and play their monosystems, and I wanted to capture that energy'.

Friday, September 30, 2022

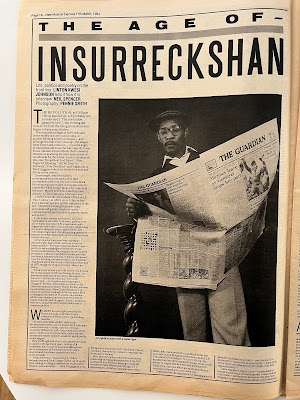

The Age of Insurreckshan - LKJ in NME, 1984

|

| Ad for LKJ's Making History LP from same issue of paper |

Monday, April 25, 2022

Linton Kwesi Johnson interview, 1982

Saturday, April 02, 2022

Life Between Islands

Images of musicking and dancing feature heavily in the exhibition 'Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art' at Tate Britain.

|

| Paul Dash - 'Dance at Reading Town Hall' (1965). Dash played piano in a band, the Carib Six - this is a view from the stage. |

|

| Tam Joseph - 'The Spirit of Carnival' (1982) |

|

| Denzil Forrester - 'Jah Shaka' (1983) |

|

| from Liz Johnson Artur, 'Lord of the Decks' featuring photos from the early UK grime scene. |

'The various musical styles created in widely defined Black Atlantic history have proved so influential that we are obliged to consider the consistency with which they have summoned the possibility of better worlds, directing precious images of an alternative order against the existing miseries, raciological terrors and routine wrongs of capitalist exploitation, racial immiseration and colonial injustice. Those gestures of dissent and opposition were voiced in distinctive keys and modes. They carried the cruel imprint of slavery and were influenced by the burden of its negation.

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

Re-appreciating Bob Marley after Marlon James

|

| Bob Marley mural by Dale Grimshaw near to Brockley station, South London. This was painted this year to replace a previous Marley mural that was demolished. Its painting was contentious locally. Marley had no particular connection to this place, but as with all Marley-related matters it's what he symbolises that many find significant - in this case a visual link to the area's African Caribbean recent history in a period when it is arguably become more white/middle class. |

|

| Pragaash perform in front of Marley backdrop |

Sunday, September 08, 2013

Mass arrest of anti-fascists opposing the EDL in Tower Hamlets

|

| Large police presence on corner of Tower Bridge Road and Queen Elizabeth St SE1 - EDL gathering point |

|

| 'Sisters Against the EDL' |

|

| South London Anti-Fascists Banner |

Saturday, April 27, 2013

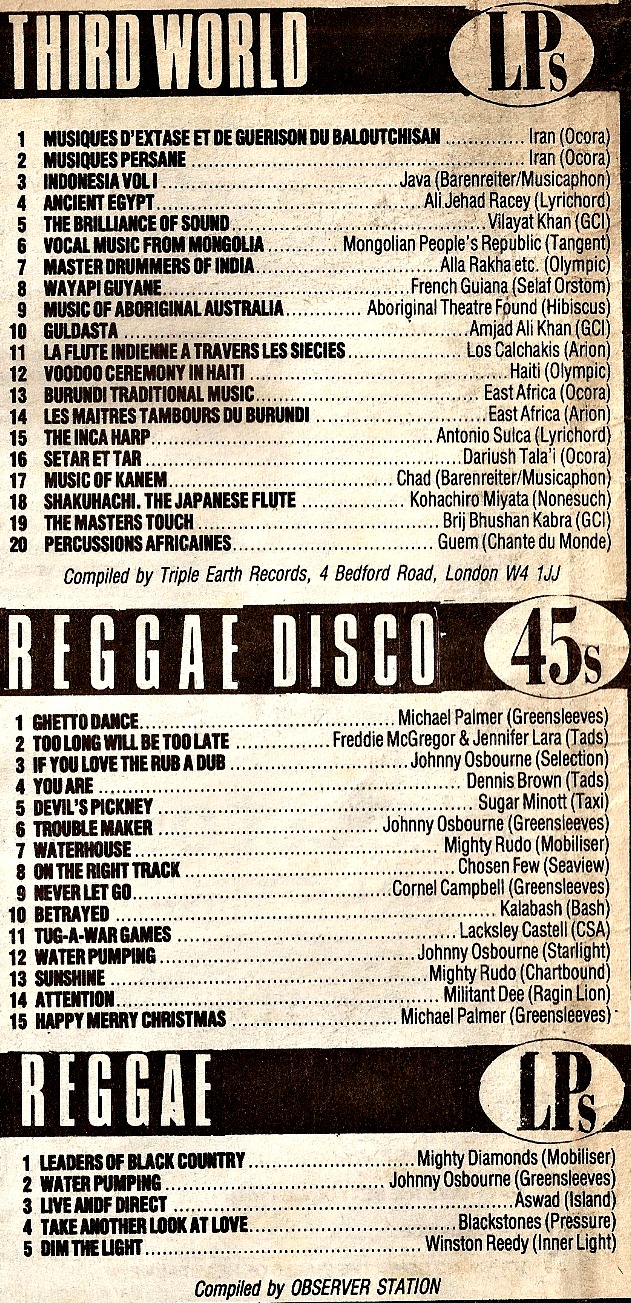

NME Charts December 1983: the best of times and the worst of times?

Wednesday, November 07, 2012

History is Made at Night Sampler 1.0 - a zine for the bookfair

Monday, May 28, 2012

NME Guide to Rock & Roll London (1978): Reggae

I'm going to scan it and put some of it up over the next few weeks, starting with this guide to reggae venues and shops in the capital at that time. The listed venues include Dougie's Hideaway Club in Archway N18, Club Noreik in Seven Sisters Road N15 and the Bouncing Ball Club (43 Peckham High Street SE15), the latter offering 'Good Bar, plus hot Jamaica patties. Spacious club with congenial atmosphere, featuring top-line JA and UK reggae acts, plus some soul. Admiral Ken Sounds'.

Reggae record shops included Hawkeye in Harlesden, Daddy Kool (Tottenham Court Road), M&D (36a Dalston Lane E8), Greensleeves (Shepherds Bush), Dub Vendor (Clapham Junction market - which survived in the area until last year), Third World Records (113 Stoke Newington Road N16) and Tops Record Shop (120 Acre Lane, SW2) - 'Front Line rock at Tops, the leading South London dub stop stockists of all current reggae releases, plus R&B and doo-wop albums, soul imports, and a fortnightly shipment of JA pre, specialising in Techniques (JA) and Clintones (US) productions'.

See also:

NME Guide to Rock & Roll London 1978: Gay Clubs

NME Guide to Rock & Roll London 1978: Disco

Sunday, May 06, 2012

We are Luton

Friday, January 20, 2012

Winston Riley (RIP) and Stalag 17

'Winston Riley, an innovative reggae musician and producer, has died of complications from a gunshot wound to the head. He was 65. Riley died Thursday at University Hospital of the West Indies, where he had been a patient since November, when he was shot at his house in an upscale neighborhood in the capital of Kingston, his son Kurt Riley said Friday. Riley also had been shot in August and was stabbed in September last year. His record store in Kingston’s downtown business district also was burned down several years ago. Police have said they know of no motives and have not arrested anyone'.

But you've got to love the man who produced this...

...and this:

...not to mention this...

Stalag 17

Riley's Stalag 17 Riddim has been used as the basis for these and countless other reggae, dancehall and indeed hip-hop tracks (see for instance list at Jamaican Riddim Directory). I believe the original Stalag 17 track, recorded by by Ansell Collins and produced by Riley, dates from 1973. Riley himself put out a compilation album of versions called Stalag 17, 18 and 19, and later there was a tribute album Stalag 20, 21 and 22.

An intriguing question is why the orginal instrumental track was called Stalag 17 in the first place. Clearly it took its name from the 1953 movie about US prisoners of war in a German camp during World War Two; the film in turn taking its name from a real POW camp at Krems in Austria.

I suspect that the name simply reflected the continuing importance of World War Two in popular culture in that period. In England, children in the 1960s and early 70s grew up on a never ending diet of war movies and no doubt it was similar in Jamaica, from where thousands of people had left to fight in the war. Other Jamaicans had travelled to work in US factories and farms during the war - incidentally some of them being detained in camps and punished for 'breaking contracts', a policy that led to a 1945 riot by 1,000 Jamaican and Bahamian workers in Camp Murphy in West Palm Beach, Florida.

Of course The Skatalites had previously covered the theme tune to another war movie, The Guns of Navarone, getting a UK hit in 1967. Later, in 1978, The Clash reworked the theme tune from Stalag 17 - Johnny Comes Marching Home - as English Civil War.

Anyway, there's a sweet irony in the name given by the Nazis to a prison camp being appropriated by people they would doubtless have regarded as 'racially inferior' for not just one track but a whole sub-genre of African Caribbean music. Billboard obituary here

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Dancehall and church hall

In respect of the latter, Beckford recalls his first encounter with dub courtesy of Coventry's Conquering Lion sound system in the 1970s:

'What immediately struck me when I entered the converted class-room masquerading as an urban dance floor was the sheer intensity of the event. It was corked full of young people and the events were conducted in pitch dark. It was also boiling hot due in part to the reggae dance floor chic of wearing winter coats with matching headwear. However, overpowering all of my senses was what Julian Henriques terms sonic dominance of the sound system. There was a throbbing, pulsing bass line ricocheting through the bricks, mortar, flesh and bones. The sonic power was tamed in part by the DJ's improvised poetic narration or 'toasting' over the dub track. Playing on the turntable was a dub version of MPLA by a reggae artist called 'Tappa Zukie' (David Sinclair). As the DJ 'toasted', the silhouetted bodies moved in unison to the bass line: the heat, darkness and body sweat adding to the sheer pleasure of this Black teen spirit... These rituals of orality, physicality and communality were also acts of pleasure and healing'.

Beckford is also good on the sound systems as means of cultural production: 'Sound systems consist of far more than just turntables and speakers. Such is their size and complexity that they require a crew of people to run them' (operators, selectors, DJs, drivers etc), and 'this is an important point of departure from the current trend in mainstream popular DJ culture where DJs travel with records and play on sets already pre-prepared and with which they have no relationship... As well as being a community, the sound sysyem's division of labour provides an opportunity for artistic development'.

If the theological aspects of the book sound like a turn-off I recommend sticking with it. Beckford attempts the ambitious task of 'dubbing' pentecostalist Christianity with a bit of help from 'Black liberation theologies of the Black Atlantic' (James H Cone, Gutierrez etc.) as well as Paul Gilroy, Deleuze and Guattari.

If you think it's stretching it a bit to describe Jesus as 'a dubbist involved in taking apart and reconstructing. human life and transforming unjust social structures and practices', you should at least be open to having some of your prejudices challenged. It certainly gave me pause for thought and made me a bit more sceptical of the assumption that proliferating black churches are simply a sign of political quietism if not reaction, even more so of the assumption that the leisure choices of white middle class urbanites (arthouse cinemas, restaurants) should always be given precedence*.

(*Obviously I'm referring here to the typical local liberal campaign that goes 'omg that long derelict building is being turned into an African church we must start a campaign to turn it into something we like instead'. I don't dispute that some churches are money making rackets with dubious practices in relation to child 'possession' etc. but that's hardly the whole story!)

Monday, August 08, 2011

Shashamene 1982

The news today from Ethiopia is grim, as it has been at many times in the past, with drought, food shortages, torture and political repression. Yet this place has also been the focus of utopian hopes, not least from the Rastafarian movement. The Face magazine (November 1982) featured a fascinating article by Derek Bishton about Shashamene, a township in southern Ethiopia where Rastafarians from Jamaica and elsewhere had settled in search of a better life.

As the article explains, the origin of the setlement was the 1945 Land Grant, whereby Ethiopian head of state Haile Selassie donated 500 acres of land to enable black people from elsewhere to return to Africa. This had followed discussions with the Ethiopian World Federation, a Garveyite organisation set up to support Ethiopia after it was invaded by Mussolini's Italy in 1935.

By the mid 1970s there were only about 15 Rastafarians living in Shashamene, but they were then joined by a second wave associated with the Twelve Tribes of Israel, the group that Bob Marley was associated with. The article documents their lives and hopes, as well as their struggles in the face of poverty, political tensions, and internecine quarrels. Not sure how life is now in Shashamene, but the Rastafarian settlement is still in existence.

For more on Shashamene today and its musical connections with Ethiopian reggae, see this great post at Soundclash

(click on pages to enlarge and read article)