'Sixteen people will face criminal charges in connection with a deadly fire at a Brazil nightclub in January. More than 240 people were killed when insulation foam caught fire and spread toxic fumes through the packed venue in the southern town of Santa Maria. Police said the blaze started when the singer of a band held a firework close to the ceiling, which then caught fire. The singer, the band's producer, the club's owners, and fire officials will be charged with negligent homicide. A police report published on Friday said dozens of eyewitnesses reported seeing the singer on stage holding the firework which triggered the blaze. Attempts by the singer and a security guard to extinguish the fire failed when the extinguisher they used did not work, the witnesses described.

Many said that the security guards at the Kiss nightclub at first tried to stop people from leaving the club. The fact that the club only had one door was described by the investigators compiling the report as a "grotesque safety failure". Escape routes and lighting in the club were also found to be inadequate. The club was found to be overcrowded. Eyewitnesses reporting more than 1,000 revellers packed into the venue, which had a licence for fewer than 800. All of the 241 victims were found to have died of asphyxiation as toxic fumes from the insulation foam quickly spread through the club. Police believe that five of those killed were people who had gone into the club to try to rescue others. More than 600 people were injured' (BBC News, 22 March 2013).

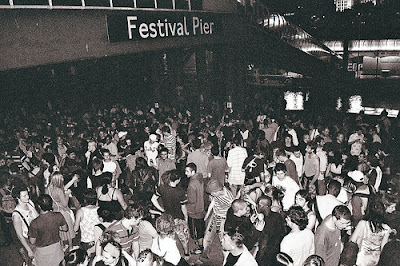

|

| Thousands pause outside the Kiss nightlub in Santa Maria on a march after the fire |

St Laurent du Pont, France, 1970

'A fire at a nightclub in France has killed 142 people, most of them teenagers. The club, a mile from the town of St Laurent du Pont, near Grenoble, was packed with revellers when the fire started at around 0145 local time (0045 GMT). A fire department spokesman said the partly-wooden building "went up like a box of matches" and the victims perished within 10 minutes. Many of the interior fittings, including the ceiling, were flammable, the spokesman said, but many people might have escaped from the Club Cinq-Sept had emergency exits not been blocked. Firefighters found bodies piled five deep around the exits which had been padlocked and barred with planks to keep out gatecrashers.

It is believed some dancers were trampled to death in a stampede as people rushed to get out of the dance hall through the main entrance. Only 60 of the 180 people in the building are believed to have escaped - many of them are in hospital with up to 90% burns. Herve Bozonnet, who got out virtually unscathed, said: "It was ghastly. People on the dance floor were engulfed by burning plastic from the ceiling." Another survivor, 17-year-old Dominique Guette, said: "We tried to break down emergency exits but it was impossible." (BBC News, 1 November 1970)

Guy Debord on the Saint Saint-Laurent-du-Pont Fire

'The instantaneous incineration of the dance club in Saint-Laurent-du-Pont, in which 146 people were burned alive on 1 November 1970, certainly aroused strong emotions in France, but the very nature of these emotions has been poorly analyzed, then and now, by many commentators. Of course, the incompetence of the authorities concerning security instruction has been revealed: these instructions are well conceived and minutely spelled out, but making them respected is quite another matter because, effectively applied, they more or less seriously interfere with the realization of profits, that is to say, the exclusive goal of capitalist enterprises in both their places of production and the diverse factories in which diversions are distributed or consumed. The dangerous character of modern [building] materials and the propensity for horrible decor to become the decor of horror have already been noted: "One knows that the polyester ceilings, the use of plastic covering on the walls and the inflatable seats burned like straw and cut off the retreat of the dancers, who were surprised in their race against death" (Le Figaro, 2 November 1970).

.... many people have been sensitive to the particular horror of exit denied to all those who flee, already on fire or close to it, by a barrier specially created to only open towards the interior and to close again after the passage of each individual: it is a question of avoiding the situation in which someone might enter without paying. The slogan on the signs carried by the parents of the victims a month later - "They paid to enter, they should have been able to leave" - seems to be obvious in human terms, but it is fitting to not forget that this is not obvious from the point of view of political economy, and the difference between these two projects is only and simply knowing which one will be the strongest. Indeed, to enter and to paid is the absolute necessity of the market system; this is the only necessity that it wants and the only one that preoccupies it. To enter without paying is to put the market system to death. To enjoy oneself (or not) on the inside of the air-conditioned trap, to possibly leave it - all this has no importance for it, nor even any reality. At Saint-Laurent-du-Pont, the insecurity of the people was only the slightly undesirable by-product - the nearly negligible cost - of the security of the commodity...'

Originally written in 1971, for publication in the 13th (never published) issue of Internationale Situationniste. Translated by NOT BORED!

See also: 2009 fire in Perm, Russia; 2008 Shenzhen fire, China/2004 Buenos Aires fire