Wednesday, October 09, 2024

Big Sexy Festy Finsbury Park (and Big Chill) 1996

Tuesday, January 02, 2024

Left at the Pier Festival, Brighton 1994

A feature of the 1980s and 1990s in England was officially sponsored free music festivals, usually one day affairs supported by local councils or other organisations such as trade unions. One such event was the Left at the Pier Festival held on the seafront at Brighton as a 'festival to celebrate public services' and sponsored by Southern and Eastern Regions of the Trades Union Congress and the Workers Beer Company.

The bands playing at this festival would have been familiar at many summer festivals in this period, including Dreadzone, Tribal Drift, Bhundu Boys, the Oyster Band, Co-Creators and Transglobal Underground. I remember seeing the latter two on a hot afternoon, with a big screen showing action from the World Cup then taking place in the USA. I was staying in Brighton at the time taking part in an international conference (AIDS Impact: Biopsychosocial aspects of HIV Infection).

Thursday, May 25, 2023

Bedroll Bella: Geordie raver

Bedroll Bella by Sid Waddell (Sphere, 1973) is the story of a feisty, foul mouthed, hard drinking, 'right raver' and proud Geordie 'lass' who runs away from home in search of teenage kicks. She falls in with a bunch of 'bedrollers', itinerant hippies who drink, fight, screw and sleep rough in the ruins of Scarborough Castle by night and shoplift by day (carrying around their rolled up bedding - hence the name). Published in the youthsploitation publishing boom, it sits alongside the works of Richard Allen and Mick Norman in depicting a world of 'knockers', 'birds' and 'having it off' in alleyways and pub car parks; a world of casual violence, with scraps with Hells Angels and rugby club types. The book was apparently barred from the shelves of WH Smith when it came out. Bella is also a poet on the side, composing a sonnet in lipstick on a bathroom window. Like her the author also has higher literary ambitions. Naturally a visit to Whtiby entails a mention of Bram Stoker.

Other than the sexual politics, the thing that jars the early 21st century reader is its industrial background. The backdrop is the shipyards and mines of the north east, presented as being at the heart of local identity. The freaks are not middle class drop outs (as 'hippies' are usually portrayed) but have taken to the road as an alternative to dead end jobs, the dole and stifling conformity: 'She wanted faces and figures with style, animation, excitement.... anything different. There had to be a lifeline somewhere, a raft to sweep her out of boredom and the prospect of the dole'.

Class is at the heart of the novel. Bella, whose dad is a boilermaker, argues with a teacher's comments about greedy strikers: 'them and the miners only get a living wage by striking - and striking hard... So feeding me and my mother and seeing we've got shoes and coal is greed, eh, miss?' .

Spider, the main male character, is the son of a miner (like the author). When he reads in the paper about miners dying in a disaster in Poland, he is consumed with rage: 'The death of a miner is about as important as the death of a worm under a spade. Both are an occupational hazard. Self-pity welled in Spider's breast. How could society expect a pitman's son to be anything other than a dirty, sweaty, scruffy hippy? He had never known anything better. And if he followed his dad into the hole, who would have thanked him? Alf Robens? Ted Heath? Harold Wilson. No, not fucking likely. They were the coal-owners now. They didn't give a monkey's nut. Spider wanted to talk. To get some of the green bile of class hatred of his chest.' He manages this by having sex in a train toilet with the posh 'Weekend Madonna' character, a part time hippy who slums it at the weekend and then returns home in the week.

In a key section of the book Bella and co. head to the Yorkshire Folk, Blues & Jazz Festival, a real event held at Krumlin near Halifax in August 1970, reputed to have been hit by some of the worst weather even seen at a British festival. Before the rain comes down, Bella has that festival epiphany feeling: 'Bella was tripping out. She had never felt so entirely conjoined with society before. She was part of the primeval soup, and Spider was the umbilical cord stringing her to this wild, wondrous world. Being part of it was quintessence. It was not a case of wanting the kicks of drugs, music or men. It was deeper, more heady, wine, the scene was feeding her. This was the pure juice of the fruit. She was on her way to Heaven, and by Christ she was gonna be moved... Bella wanted to cry. For the first time in her life she knew why sparks like Wordsworth and Chaucer and even that maniac Swinburne, who she'd had to study for O levels, had written poetry. It was all here on the grass, naked and pulsating. The Daffodils, the Pardoners and Summoners and even the Hound of Heaven... The pale, streaked bleached look of the moorland sky and turf was enhanced by the gear the kids wore. Vests and stained blue jeans, Army surplus anoraks, nothing that quite fitted. Clothes had to hang, so that the loose slim bodies could flow along as freely as their hair swung... To be alive was very heaven'.

I believe this was Waddell's only novel, though he went on to find fame as a TV sports commentator, his name being synonymous with coverage of darts in Britain up until his death in 2012. His politics remained intact until the end - asked in 2007 to imagine 'If you'd been present as a commentator when Maggie Thatcher left No 10 for the last time, what line of commentary would you have given?' he replied: "Sooo the poor little Iron Lady ends her years of vicious tyranny sobbing in a posh car. She took the kids' milk, made the rich richer and she smashed the coal miners... what a magnificent legacy!"

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

Hackney Volcano Festival 2000

Continuing series of scanning in old flyers of things I went to in ancient times, or should I say documenting priceless cultural history artifacts, here's the programme for Hackney Volcano Festival held on Hackney marshes in August 2000.

This was a legal free festival, seemingly with some Millennium related funding, but featured lots of performers, sound systems etc. from the free party, punk and other scenes. The line up included for instance Luton's Exodus Collective, Out of Order Sound System (with Liberator DJs), Hackney punk system Reknaw and Homegrown radio (UK hip-hop). Reggae writer Penny Reel was on the Solution Sound System and Bobby Friction was on 'Purple Banana's Conscious Clubbing stage'. Squatting/festival magazine Squall was trying to 'put some revolutionary stance back in the dance' and bands included benefit gig stalwarts P.A.I.N., Inner Terrestrials and The Astronauts. Quite a cross section of turn of the century London musical subcultures. Shame I can only really remember the Miniscule of Sound - 'the world's smallest nightclub' - a tiny booth with a disco ball!

Saturday, October 08, 2022

'We are dancing strong': A free festival on Hackney Marshes, 1997

|

| 'The Big Sexy Festy Party' |

|

| Daniel Poole glow in the dark robot t-shirt! |

Sunday, April 15, 2012

Festivals Britannia

What lifted it was the film footage of these events and an excellent range of interviewees including many of the key figures in the different phase of the 20th century counter culture. Jazz ravers Acker Bilk and Kenny Ball recalled the 1950s jazz festivals, the later remembering 'you couldn't have a rave up in a dancefall. You had to walk across a floor and ask a girl to have a waltz or something, but if you were in a field you felt free'.

The Beaulieu jazz festival in Hampshire started out in 1956. In 1960, simmering tensions between modern and trad jazz fans sparked off the so-called Battle of Beaulieu with fans impatient to hear some Acker demolishing a BBC TV tower. A contemporary newspaper reported: 'Jazz succumbs to the Hooligans'. In the same period the annual Aldermaston 'Ban the Bomb' marches became what free festival veteran Sid Rawle termed 'a festival on the march'.

The late 1960s free concerts in London's Hyde Park were described by Roy Harper as the high point of the hippie moment, a time when 'everything seemed to be bright and in the process of awakening' (Roy Harper). On the Isle of Wight, the 1970 paying festival famously ended up with those outside storming the fence so that it was opened up for free on the final day. Festival organisers and Mick Farren who was on the fence storming side were interviewed, but the best quote was amongst a selection seemingly from a series of Isle of Wight residents engraged by the 'invasion' of the area by 600,000 mostly young people: 'If you have a festival with all the stops pulled out, kids running around naked, fucking in the bushes, and doing every damn thing that they feel inclined to do I don't know that's particularly good for the body politic' (all delivered in an impeccable upper class accent - I assume this was never broadcast at the time)

|

| Windsor 1974 - 'Hippie PC Flees Pop Fury' (from the excellent UK Rock Festivals site) |

In the early 1970s the first Glastonbury festivals were followed by the emergence of the free festival circuit, most notably the Windor Free Festival. Closed down in a major police operation in 1974, the next year the Government offered a disused air force base at Watchfield in Oxfordshire as an alternative - but a state-sponsored 'free' festival with police on site was not quite the same. Among those recalling this period on the film were Nik Turner and Stacia from Hawkwind and Penny Rimbaud from Crass.

The free festival scene was dealt a severe blow with the mid-1980s crackdown on the Stonehenge Festival and the Convoy - everybody should have to watch the bullying gratuitous violence of the police in the so-called Battle of the Beanfield to understand the state of virtual social war in the mid-1980s, with the Government giving its forces free reign to bash miners, travellers and other 'enemies within' with impunity (sometimes feels like we are heading into a similar period).

The outlaw tribes, disenchanted and disenfranchised needed to find other places to gather, and Glastonbury had relaunched in the 1980s as paying festival raising money for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Farmer and festival organiser Michael Eavis reflected that 'we were just anti-Tory really, we were on a crusade to take on Maggie and to fight the oppression and it was very effective'. Through much of the 1980s it wasn't that hard to sneak into the festival for free, but increasing pressure from the Council and the police required stronger fences and more security.

By the early 1990s the survivors of the free festival scene were joining up with the new sound system culture, as described by Mark Harrison from Spiral Tribe and Rick Down (Digs) from DIY Sound System. The huge 1992 Castlemorton free party/festival prompted the Government to introduce the Criminal Justice Act to clamp down on 'raves'.

The programme ends with the increasing dominance and prevalence of commercial festivals in the noughties. But there is some evidence that this boom has peaked, with the Guardian asking recently 'Have we fallen out of love with the great British music festival?'. I don't think the desire to gather under the skies with thousands of like-minded music lovers has changed, but more and more of us can't really afford to spend the cost of a holiday on a weekend, especially if that weekend has to be spent in a highly corporate fenced-off enclosure.

Sunday, April 08, 2012

Hackney Homeless Festival 1994

In the early/mid 1990s there were some big free festivals in London parks. Not pseudo-free festivals behind big fences with lots of private security, but proper sprawling mildy-chaotic events with sound systems, dance tents and lots of bands. Two of the biggest were the Deptford Urban Free Festival (in Fordham Park, New Cross) and the Hackney Homeless Festival.

The latter in Clissold Park, Stoke Newington in May 1994 aimed to raise awareness of homelessness, as the name suggests. The energy behind it came out of the squatting scene, but they did involve a locla street homeless hostel, McNaughton House. Up to 30,000 people attended with acts including The Levellers, Co-Creators, Spannerman, Back to the Planet and Fun Da-Mental. One of the stages was organised by Club Dog.

The police piled in after the festival outside the Robinson Crusoe pub, arresting 30 people as clashes erupted. According to one person present: 'A line of police in riot gear approached the pub, pushing people, telling them to go. That's when the glasses started flying. I saw one guy, who asked why they were doing this, get jabbed with a baton. I saw a woman in a wheelchair, who was obviously very distressed, being wheeled around roughly by a police policeman. It was completely unprovoked' (NME, 14 May 1994 - full article below)

Some interesting video footage of the festival at Spectacle video archive.

For more on Hackney, see Radical History of Hackney: http://hackneyhistory.wordpress.com/

Friday, February 17, 2012

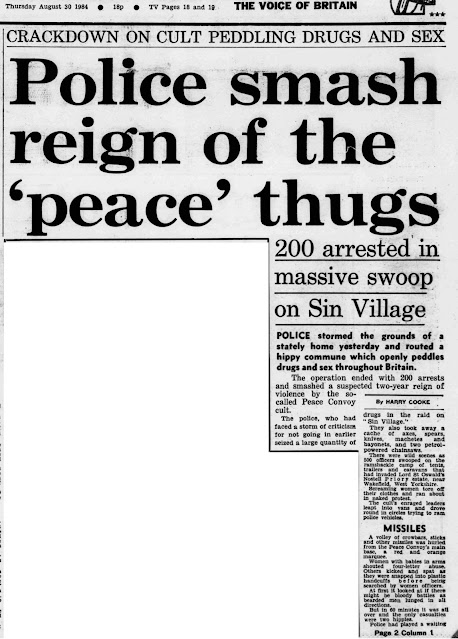

Nostell Priory Festival 1984: Police attack Convoy

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Electric Eden

Young is less interested though in ‘folk’ as a specific musical genre, than in the vision he sees underlying it - the use of music as a form of ‘imaginative time travel’ to the ‘succession of golden ages’ (both semi-historical and entirely fictional), found in British culture – Merrie England, Albion, Middle Earth, Avalon, Narnia. As he states in the introduction ‘The ‘Visionary Music’ involved in this book’s title refers to any music that contributes to this sensation of travel between time zones, of retreat to a secret garden, in order to draw strength and inspiration for facing the future’.

This is not a characteristic solely of what is normally defined as ‘folk music’ and he includes within it dreamy English psychedelia, and the work of later visionary musical outsiders such as Kate Bush and Julian Cope.

The stories of Cecil Sharp and Ewen McColl have already been well documented, for me the most interesting parts of the book deal with the subsequent trajectories of late 1960s/1970s folk rock and ‘acid folk’, with their infusions of both Early Music and futuristic psychedelia. As well as covering the obvious reference points (Fairport Convention, Pentangle, Incredible String Band, Nick Drake), Young gives space to many less well known artists such as Bill Fay, Comus and Mr Fox.

After languishing in relative obscurity for many years, some of these have only recently secured the listeners denied them at the time. In another form of time travel, it’s almost as if some of the albums recorded in the late 1960s/70s were set down as ‘time capsules’, to be unheard in their present but acting as a gift to the future that would appreciate them. The paradigmatic examples are of course Nick Drake, who only achieved posthumous fame when his fruit was in the ground, and Vashti Bunyan, whose Just Another Diamond Day sold only a few hundred copies in 1970s and who has only really gained widespread recognition in the last five years or so. I saw her give one of her first major performances at the Folk Britannia 'Daughters of Albion' event at the Barbican in London in 2006, alongside Eliza Carthy, Norma Waterson, Kathryn Williams, Sheila Chandra and Lou Rhodes.

Places and Spaces

Young is very good on place – both the specific landscapes that influenced particular musicans, and the spaces where music was performed. In relation to the former he mentions for instance Maiden Castle in Dorset, inspiration for John Ireland’s Mai-Dun (as well as incidentally the novel Maiden Castle by John Cowper Powys, an author with a similar take on the visionary landscape).

In relation to the latter, he mentions clubs such as Ewen McColl’s Ballads and Blues club/Hootennanay upstairs in the Princess Louise pub in Holborn (founded in 1957) and its later evolution into The Singers Club at the Pindar of Wakefield on Grays Inn Road. In Soho, Russell Quaye’s Skiffle Cellar at 49 Greek Street (1958-60), was replaced at the same address in 1965 by ‘the poky palace of Les Cousins, where the folk monarchy held court, audiences of no more than 150 were routinely treated to mystically revelatory performances. The club never got around to applying for a liquor licence, so patrons consumed tea and sandwiches in a haze of hash smoke, straining to hear the soloists over percussive effects from the cash register’. Denizens included Bert Jansch, Davy Graham, Simon & Garfunkel, John Martyn, Martin Carthy and Roy Harper.

Outside of London in the 1960s, ‘Hertfordshire was already one of the most influential hotbeds of the new folk movement outside of Soho… Herts heads keen for a lungful of marijuana and subterranean entertainment would gather at the Cock in St Albans… Down the road from The Cock brooded the Peahen, where a more traditional, MacColl-style folk-revival club was held’. In nearby Hemel Hempstead, singer Mick Softley ran the Spinning Wheel, while at the Dolphin Coffee Bar, Pete Frame opened Luton Folk Club in 1965.

There's also a good chapter on free festivals, 'Paradise Enclosed', as 'a serious attempt to stake out and remake Utopia in an English field. The temporary tented villages of Britain's outdoor festivals represented a practical attempt to live out the dream of Albion' two hundred years after the Inclosures Act of 1761 and the enclosure of common land.

Some criticisms

In a work of this scale and scope there are bound to be some factual errors of geography (Luton is in Bedfordshire not Hertfordshire) and history (Aleister Crowley was not the founder, or even a founder, of the Golden Dawn). But these are minor quibbles.

There are though a few problems with the framework Young uses for all this rich material. The chief one is its use of the term ‘Britain’s visionary music’ when it is clear that what he is describing is primarily an English phenomenon. Of course there has been plenty of folk music from other parts of the British Isles, but Young barely mentions it. In any event, it has often had a different aesthetic, concerned precisely to differentiate itself from Englishness and commemorating historical conflicts with the 'English' state from Bannockburn to the clearances (in the case of Scottish music).

Although Ireland is clearly not part of Britain, its influence on English folk is also largely unacknowledged here. Did the raucous Dubliners influence those who wanted to take folk in a more rocky direction? Did Irish rebel song envy inspire English political song (Dominic Behan was a key figure in the Singers Club)? Wasn't Thin Lizzy's Whiskey in the Jar one of the biggest folk rock hits? This is left unexplored, and arguably the greatest London folk band of all time - The Pogues - don't even get mentioned.

Young is a better musicologist than a folklorist, and while he is clearly aware that claims of an unbroken folk music tradition stretching back into the mists of time are highly questionable, he seems to want to hold on to some notion of 'pagan survivals' in folk. Despite citing Ronald Hutton in the footnotes, he disregards Hutton's findings that we know very little about the pre-Christian beliefs of the British Isles. Instead he repeats the whole Golden Bough/Wasteland mythology of ritual sacrifice as it if were fact: ‘The gods controlling these cycles needed to be appeased with sacrifices. At first, the leader of the pack, the king himself, was slaughtered before his vital energies began to die off, and a new healthy replacement was appointed in his place’.

Finally, Young does not really explore the potential dark side of all this dabbling with blood and soil. He may be right that many of those working within the folk idiom ‘have been radical spirits, aligned with the political left or just fundamentally unconventional and progressive in outlook’ – something that applies not just to the post-1950s Communist Party revivalists but to earlier pioneers such as Holst and Vaughan Williams who, as Young mentions, hung out with William Morris’s socialist circle in Hammersmith. But it is also true that this look backwards to a pre-capitalist idyll can be profoundly reactionary, and potentially very right wing. In a brief survey of current trends, Young mentions the post-industrial 'neo-folk' scene, but does not refer to the controversies over some of the neo-fascist elements involved (see the new Who Makes the Nazis? blog for more on that).

Now I've read the book (all 664 pages), I will no doubt be spending the rest of the year tracking down some of the music in it that I haven't heard yet.

(see also review at Transpontine of some of the South East London connections)

Wednesday, September 08, 2010

Sid Rawle: death of a free festival veteran

There's a very informative post by Andy Worthington at his site about Sid's life and times. As Andy says:

'Sid played a major part in the British counter-culture from the 1960s until his death, although he is, of course, best known for his involvement in the free festival movement, first at Windsor, from 1972 to 1974, and then at Stonehenge, until the violent suppression of the festival in 1985. The author and activist Jeremy Sandford (who died in 2003) described him as “the squatter to end them all, having squatted flats, houses, commons, forests, a village, boats, an island, an army camp, Windsor Great Park".'

Read Andy's full post, RIP Sid Rawle, Land Reformer, Free Festival Pioneer, Stonehenge Stalwart. See also Ian Bone, Turn Left at the Bridge. Not an uncontroversial figure, he was identified by the media as a leader of the hippies and his role in attempting to mediate with the authorities earned him criticism from some quarters - stilll, nobody can say he didn't try and make the world a more interesting place.

Thursday, August 26, 2010

Grassroots: another festival bites the dust

'Yet another independent festival has been cancelled after a concerted campaign by bureaucrats, nimbys and police. The Grassroots Feastival was a small volunteer-run event due to take place in Cambridgeshire in early September. Organisers had lined up three days of revelry, from poetry to Drum ‘n’ Bass and culminating in a communal banquet replete with juggling waiters.

The Festival faced determined opposition from the very start. According to one of the organisers, Mooney, when the application process began in January the council made it clear they would do all they could to stop the festival taking place. Martin Ford from the Police licensing board went one step further and told organisers, “I’d rather put pins in my eyes than have this festival in my county.” Mooney said, “They didn’t want it to happen so they played their games. They couldn’t use legislation so instead they used dirty tactics.” The now familiar modus operandi involved heaping ludicrous demand after ludicrous demand on organisers and stalling for time to the point that the festival risked financial ruin if they pressed ahead.

After the initial consultation, organisers met monthly with the local authorities and there were six revisions of the festival’s management plan in total. Each time they were presented with ever more unreasonable conditions, ranging from heras-fencing the A11 in case of invasion by wandering partygoers who had strayed three miles over fence and field, to installing security watchtowers (with or without machine gun nests) to ensure the unruly throng of 2000 didn’t erupt in spontaneous revolution.

Each time, organisers either met the conditions or managed to argue their case that what they were being asked was beyond the realms of sanity or reason. However the killer blow came with the final application for a licence. When handing in the application, local authorities clearly told organisers that they only needed to submit one paper copy and that the pack of other relevant licensing bodies, such as traffic management and the fire brigade, would be happy with an emailed copy. At the eleventh hour of the last day they had to submit the application, organisers were then told that the licence would be refused unless all the bodies had paper copies. With no time left to do this, organisers would have had to resubmit and wouldn’t have received a decision until just days before the festival. If the licence had been refused at that point it would have spelled financial disaster for all involved and so organisers were left with no choice but to cancel.

A despondent Mooney told SchNEWS, “In some countries people welcome celebrations.” After the attacks on Strawberry Fair (see SchNEWS 715), the Big Green Gathering (SchNEWS 685), UK Teknival (SchNEWS 727) and Thimbleberry (SchNEWS 707) amongst others, it is becoming increasingly clear the UK isn’t one of them'.

Monday, August 09, 2010

Some sheep, some homeboys and a funki dred

On the Saturday, musical highlights included an acoustic set from the Alabama 3 and a DJ set from Jazzie B/Soul II Soul.

The former (pictured above) might have made it on the global stage via providing the theme tune to The Sopranos but they are very much the house band to Brixton druggies, drinkers, post-ravers, mental health system survivors and (as)sorted radicals. They started out with a singalong 'You are my Brixton' before moving on via Woke up this Morning to a modified Johhny Cash cover - Brixton Prison Blues.

Alabama 3 always like to support good political causes, including prisoners in miscarriage of justice cases. This time the focus was on a struggle closer to home, with singer Larry Love being joined by his kids to voice opposition to the threatened closure of the Triangle Adventure Playground by the Oval.

Jazzie B was joined by MC Chickaboo for a wide ranging set that got the crowd dancing to mash ups of Kellis's Milkshake with Billy Jean; and Seven Nation Army with Public Enemy's Bring the Noise, among others. Further ingredients in the mix included James Brown, Dizzee Rascal, Beyonce, Deelite, Nirvana and Ray Charles. All of this plus tantalising snatches of his hits with Soul II Soul - most notably the opening bars of Keep on Movin' followed by some heavy drum'n'bass. And yes he did sign off with the Soul II Soul motto of 'a happy face, a thumpin' bass, for a lovin' race.'

Jazzie B was joined by MC Chickaboo for a wide ranging set that got the crowd dancing to mash ups of Kellis's Milkshake with Billy Jean; and Seven Nation Army with Public Enemy's Bring the Noise, among others. Further ingredients in the mix included James Brown, Dizzee Rascal, Beyonce, Deelite, Nirvana and Ray Charles. All of this plus tantalising snatches of his hits with Soul II Soul - most notably the opening bars of Keep on Movin' followed by some heavy drum'n'bass. And yes he did sign off with the Soul II Soul motto of 'a happy face, a thumpin' bass, for a lovin' race.'

Like the Alabama 3, Soul II Soul's history is bound up with Brixton (even if Jazzie B is a north Londoner) - in their case their famous sound system Friday nights at the Fridge in the 1980s were a key stepping stone on to making their own records and international success.

Monday, December 21, 2009

Thimbleberry Festival Under Attack

On Friday 11th December 2009 Andy Norman, host and organiser of Thimbleberry Music Festival in County Durham, UK appeared in court facing the charge that he "did permit the use of cannabis on his premises". The charge relates to alleged use by the festival-goers of cannabis at the last September festival. He has not entered a plea and is due back in court on the 5th February 2010 to face committal to Crown Court.

The charge is being brought under Section 8 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. An amendment to this Act passed by the Government in 2001 made it a criminal offence for people to knowingly allow premises they own, manage, or have responsibility for, to be used by any other person for the adminstration or use of any controlled drugs.

A conviction would doubtless be used as a pretext not to grant a licence for the festival next year, and would also set a very dubious precedent. People inhale at pretty much all festivals, so presumably the police could charge anybody organising or hosting a festival with this offence.

There is a facebook group in support of the festival.

Saturday, October 03, 2009

Michael English (1941-2009)

Saturday, August 22, 2009

Festival Communication, Festival Time

Festival communication involves a major shift from the frames of everyday life that focus attention on subsistence, routine, and production to frames that foster the transformative, reciprocal, and reflexive dimensions of social life. Such a frame shift does not rule out the mundane or the dangerous; commercial transactions flourish in many festivals, and mask and costume have on occasion disguised bloody violence. The shift in frames guarantees nothing but rather transposes reality so that intuition, inversion, risk, and symbolic expression reign.

The manipulation of temporal reality

Photos of Carnaval del Pueblo in Southwark, August 2009 (a Latin American festival in South London), by love of peace (top) and vertigogen (bottom) via flickr.

Thursday, August 06, 2009

If it's called a festival, is it one?

Rarely do such events use the term festival, employing instead a name related to the stated purposes or core symbols of the event: Mardi Gras (Catholic), Sukkot (Jewish), Holi (Hindu), Shalako (Zuni), Adae (Ghanaian), Calus (Romanian), Namahage (Japanese), Cowboy Reunion (American), and Feast of Fools (French). Those events that do have festival in their titles are generally contemporary modern constructions, employing festival characteristics but serving the commercial, ideological, or political purposes of self-interested authorities or entrepreneurs' (Beverly J. Stoeltje, 'Festival' in Folklore, Cultural Performances and Popular Entertainments, ed. Richard Bauman. New York, 1992).

Interesting point, but 'authenticity' isn't everything. John Eden reviews Bestival, arguing 'Whilst I agree with History is made at night’s comments on the commercial festival boom I would never really have been up for imposing something like Stonehenge Free Festival on children. I’ll take corporate sponsorship over hells angels, drug hoovers, and police brutality any day. They can discover all of that for themselves when they get older, ha ha'.

And indeed despite my earlier comments on festivals, we shouldn't fall for the myth of the earlier 'free festivals' as some kind of communism in one field contradiction-free utopia. There was certainly plenty of buying and selling , with the corollary of the threat of violence to preserve market share, and the violence of cops preventing Stonehenge festival in the mid-1980s was prefigured by the earlier violence of biker gangs - who, for instance, beat up punks at Stonehenge in 1980. As Penny Rimbaud from Crass recalled:

'Our presence at Stonehenge attracted several hundred punks to whom the festival scene was a novelty, they, in turn, attracted interest from various factions to whom punk was equally new. The atmosphere seemed relaxed and as dusk fell, thousands of people gathered around the stage to listen to the night's music. suddenly, for no apparent reason, a group of bikers stormed the stage saying that they were not going to tolerate punks at 'Their festival'. What followed was one of the most violent and frightening experiences of our lives. Bikers armed with bottles, chains and clubs, stalked around the site viciously attacking any punk that they set eyes on. There was nowhere to hide, nowhere to escape to; all night we attempted to protect ourselves and other terrified punks from their mindless violence. There were screams of terror as people were dragged off into the darkness to be given lessons on peace and love; it was hopeless trying to save anyone because, in the blackness of the night, they were impossible to find. Meanwhile, the predominantly hippy gathering, lost in the soft blur of their stoned reality, remained oblivious of our fate'.

Saturday, August 01, 2009

Big Green Gathering Cancelled

The Big Green Gathering, a fixture in the alternative calendar, was due to return after two years this week. 15–20,000 people were expected to turn up on Wednesday (29th) to the site near Cheddar, Somerset, for Europe’s largest green event - a five-day festival promoting sustainability and renewable energy, with everything from allotments to alternative media. Hundreds of staff and volunteers are already on site, and its cancellation comes just days before gates were due to open. Organisers, most of whom work for nothing, are gutted. One told SchNEWS “We are so disappointed not to be having this year’s gathering – it means so much to so many people”.

A last-minute injunction by Mendip District Council, supported by Avon and Somerset Police, put the ki-bosh on the entire event - citing the potential for ‘crime and disorder’ and safety concerns. This was despite the fact that the festival had actually been granted a licence on the 30th of June. According to Avon and Somerset police’s website “[We] went above and beyond the call of duty to ensure this event took place.” This is of course utter bollocks. The injunction was due to be heard in the High Court in London on Monday (27th). However, before that could happen the BGG organisers surrendered the festival licence on Sunday morning. As soon as this was done a police commander at the meeting was overheard saying into his radio “Operation Fortress is go”. Police have already set up roadblocks and promised to turn festival-goers back.

Chief Inspector Paul Richards, festival liaison, later confirmed to one of the festival organisers that “This is political”, adding that the decision had been made over his head at county level. One of SchNEWS’ sources on site said that the police were frank about the fact that the closure had been planned for two weeks. “This was a blatant act of political sabotage – the Big Green Gathering is now completely bankrupt, they knew that we were going to be closed down and yet they carried on allowing us to spend money hand over fist on infrastructure”.

The BGG collapsed financially in 2007 under the weight of increased security costs. The new licensing act added an extra £120k to their costs, leaving them with a loss of £80k. Security accounted for a third of their overall overheads and the road marshalling bill rose from £5k to over £23k. In spite of these setbacks, they managed to scrape themselves back off the floor with shareholder cash and some potentially dubious corporate involvement. Every effort had been made by the gathering’s organisers to accommodate the increasingly niggling demands of police and licensing authorities. The procedure lasted over six months – just check out www.mendip.gov.uk/CommitteeMeeting.asp?id=SX9452-A782D404 for the minutes of meetings held between organisers and the authorities. Demands included a steel fence, watchtowers and perimeter patrols, having the horsedrawn field inside a ‘secure compound’ and wristbands for twelve undercover police.

At a multi-agency meeting on Thursday, police took those wristbands in order to maintain the pretence that the festival stood a chance of going ahead. A catalogue of other obstacles were also continually placed in the organiser’s path. All of the businesses associated with the BGG came under scrutiny, licensing authorities contacted South West ambulances, the Fire Brigade and the fencing contractors and asked them to get payment up front from the BGG. Needless to say this caused huge problems. Under the terms of the Licensing Act 2005, police can insist on certain security firms being used by organisers. This of course leads to a totally unhealthy hand-in-glove relationship, open to abuse. Stuart Security were forced on the BGG by police, and on Wednesday last week, they suddenly announced that they wanted 60% of their fee up front. Even though the BGG scraped the cash together, the company still wanted out. So the BGG hired another firm – against police wishes. The fact that Stuart Security rely on police approval for lucrative contracts at Glastonbury Festival, the Royal Bath & West Show, WOMAD, Reading Festival, and Glade Festival has, of course, no bearing on the matter.

The last issue at stake was road closures. Mendip District Council had insisted on road closures as part of the licensing requirements. A festival organiser contacted the highways agency to process this fairly routine request. The decision was passed to junior management who reportedly came under intense pressure not to grant the closure. As the road closures were not secured, the council were able to claim that the BGG was in breach of licence. A nice little legal stitch-up that according to one QC meant the BGG stood fuck-all chance of fighting the injunction. Of course, now that “Operation Fortress” is in full swing, there are road-blocks throughout the area. The BGG is itself a limited company and could have fought the injunction - risking no more than bankruptcy - but in a nasty twist two individuals were also named, meaning that should proceedings have gone ahead against the festival then Mendip Council would have had a claim on their assets to settle court costs. Police also threatened to place the farmer on the injunction, risking his entire livelihood.

Anyone who has ever been to the Big Green will know that the atmosphere is more like a village fete than any of the mainstream events. There is virtually no aggro. It’s more about chai and gong-massages than Stella and fisticuffs. All power is 12V solar and the amplification is correspondingly quiet. Music stops at midnight. Compare that to the 24 hr Technomuntfucks that go on with state blessing across the country. Of course it would be cynical to suggest that the BGG represents an alternative that the authorities fear. It’s a gathering place for eco-activists, where the likes of Plane Stupid and No-Borders hang out and exchange ideas while trying to avoid being button-holed by 9-11 truthers.

It’s clear now that the state views events like the Big Green in the same light as Climate Camp and the anti-G20 protests. The BGG saga is showing that there may no longer be any ‘safe’ legal spaces for us to gather. The third way of quasi-legal free-ish festivals is looking like a dead-end.

It’s clear that the Big Green has been singled out – and any gathering promoting those values or trying to organise in a grass-roots way will probably suffer the same fate once they get to a certain size. As corporate-branded Glasto has become a fixture on the mainstream calendar, like Ascot or Wimbledon, many have turned towards smaller more ‘grass-roots’ festivals. Niche festivals have bloomed across the British landscape. No matter what your bent, be it faerie wings or S&M, there’s probably a muddy weekend in a field for you. Of course this isn’t the first time that Britain’s had a thriving festival scene. See previous SchNEWS’ for how the free festival scene came under ruthless attack from the forces of Babylon (or just skin up for an old hippy and listen to them bang on about the glories of the White Goddess Fayre or Torpedo Town). Some have tried to go down the quasi-legal route, such as Strawberry Fair and even Glastonbury, until the aptly named Mean Fiddler intervened in 2002.

Unfortunately the corporate dollar is never far behind. Witness how Glastonbury went from a fence-jumping free-for-all where the festival organisers built the infrastructure, but the fly-pitchers, buskers and random naked lunatics made it a real festie rather than a fenced in, heavily policed corporate theme park. The Big Green was an exceptional festival, which managed to leap through the legal process while being crew-heavy and retaining a lot of the free-festival atmosphere (Not all of course - we still had to put up with plod wandering around site). It was a unique gathering place for fringe movements, from eco-activists to crop-circle nutters.

We’re not just banging on about festivals being free because we miss the good ‘ol days – there’s a huge difference between being a punter who has a whole experience laid on for them (e.g. Glasto’s themed areas with helpful stewards pointing you in the direction of the consumer delights), and being part of a festival/free party where everyone’s responsible for the entertainment, and even infrastructure like welfare. A crowd that feels it owns an event behaves differently to one that feels it has paid to have an experience. The fact that undercover police now feel free to operate and arrest people, without any back-up, for cannabis use or nudity (See SchNEWS 684 and 603) at festivals has a lot do with the sheep-like behaviour of punters - a mentality that our masters are keen to see enforced. In the SchNEWS office we’re hearing rumours that people aren’t going to be put off – alternative sites are being looked at and people are heading to the West Country anyway. In the words of one participant “Things are just getting interesting”. Time for the Big Black Barney?