Expect to read a lot this year about the 20th anniversary of acid house in the UK. There’s a new Danny Rampling '20 years of house' mix CD and a linked facebook group with 13,000+ members (worth a look if you’re on facebook as people have uploaded lots of great flyers). There’s also a planned flash mob event based around the premise of getting lots of people together to dance to acid house classics – on their headphones. Clearly 1988 was the year when house music really exploded in the UK, but house music itself goes back a few years further. The following article was originally published in the US magazine Out/Look in 1989, and looks at house music’s origins in the black gay clubs of Chicago in the 1980s:

The House the Kids Built: The Gay Black Imprint on American Dance Music - Anthony Thomas

America’s critical establishment has yet to acknowledge the contributions made by gay Afro-Americans. Yet black (and often white) society continues to adopt cultural and social patterns from the gay black subculture. In terms of language, turns of phrase that were once used exclusively by gay Afro-Americans have crept into the vocabulary of the larger black society; singer Gladys Knight preaches about unrequited love to her "girlfriend" in the hit "Love Overboard"'; and college rivals toss around "Miss Thing" in Spike Lee's film "School Daze."

What's also continued to emerge from the underground is the dance music of gay black America. More energetic and polyrhythmic than the sensibility of straight African-Americans, and simply more African than the sensibility of white gays, the musical sensibility of today's ‘house’ music- like that of disco and club music before it- has spread beyond the gay black subculture to influence broader musical tastes.

What exactly is house music? At a recording session for DJ International, a leading label of house music, British journalist Sheryl Garratt posed that question to the assembled artists. A veritable barrage of answers followed: "I couldn't begin to tell you what house is. You have to go to the clubs and see how people react when they hear it. It's more like a feeling that runs through, like old time religion in the way that people jus' get happy and screamin'… It's happening! ... It's Chicago's own sound.... It's rock till you drop… You might go and seek religion afterwards! It's gonna be hot, it's gonna be sweaty, and it's gonna be great, It's honest-ta-goodness, get down, low down gutsy, grabbin' type music." (1).

Like the blues and gospel, house is very Chicago. Like rap out, of New York and go-go out of D.C., house is evidence of the regionalization of black American music. Like its predecessors, disco and club, house is a scene as well as a music, black as well as gay.

But as house music goes pop, so slams the closet door that keeps the facts about its roots from public view. House, disco, and dub are not the only black music that gays have been involved in producing, nor is everyone involved in this music gay. Still, the sound, the beat, and the rhythm have risen up from the dancing sensibilities of urban gay Afro-Americans.

The music, in turn, has provided one of the underpinnings of the gay black subculture. Dance clubs are the only popular institutions of the gay black community that are separate and distinct from the institutions of the straight black majority. Unlike their white counterparts, gay black Americans, for the most part, have not redefined themselves- politically or culturally- apart from their majority community. Although political and cultural organizations of gay Afro-Americans have formed in recent years, membership in these groups remains very small and represents only a tiny minority of the gay black population. Lesbian and gay Afro-Americans still attend black churches, join black fraternities and sororities, and belong to the NAACP.

Gay black dance clubs, like New York's Paradise Garage and Chicago's Warehouse (the birthplace of house music) have staked out a social space where gay black men don't have to deal with the racist door policies at predominantly white gay clubs or the homophobia of black straight clubs. Over the last twenty years the soundtrack to this dancing revolution has been provided by disco, club, and now-house music.

Playback: The Roots of House

Although disco is most often associated with gay while men, the roots of the music actually go back to the small underground gay black clubs of New York City. During the sixties and early seventies, these clubs offered inexpensive all-night entertainment where DJs, in order to accommodate the dancing urgencies of their gay black clientele, overlapped soul and Philly (Philadelphia International) records, phasing them in and out, to form uninterrupted soundtracks for non-stop dancing. The Temptations’ 1969 hit “I Can't Get Next To You" and the O'Jays' "Back Stabbers" are classic examples of the genre of songs that were manipulated by gay black DJs. The songs' up-tempo, polyrhythmic, Latin percussion-backed grooves were well suited for the high energy, emotional, and physical dancing sensibility of the urban gay black audience.

In African and African-American music, new styles are almost always built from simple modifications of existing and respected musical styles and forms. By mixing together the best dance elements of soul and Philly records, DJs in gay black clubs had taken the first steps in the creative process that music critic Iain Chambers interprets as a marker of disco's continuity with the rhythm and blues tradition: "[In disco] the musical pulse is freed from the claustrophobic interiors of the blues and the tight scaffolding of R&B and early soul music. A looser) explicitly polyrhythmic attack pushes the blues, gospel and soul heritage into an apparently endless cycle where there is no beginning or end, just an ever-present 'now.' Disco music does not come to a halt… restricted to a three-minute single, the music would be rendered senseless. The power of disco… lay in saturating dancers and the dance floor in the continual explosion of its presence.' (2)

Although the disco pulse was born in the small gay black clubs of New York, disco music only began to gain commercial attention when it was exposed to the dance floor public of the large, predominantly white gay discos. Billboard only introduced the term disco-hit in 1973, years after disco was a staple among gay Afro-Americans, but- as music historian Tony Cummings noted- only one year after black and while gay men began to intermingle on the dance floor.

By the mid-seventies disco music production was in high gear, and many soul performers (such as Johnny Taylor with his 1976 hit "Disco Lady") had switched camps to take advantage of disco's larger market. Records were now being recorded to accomplish what DJs in gay black clubs had done earlier. Gloria Gaynor scored a breakthrough in disco technique with her 1974 album, Never Can Say Goodbye. The album treated the three songs on side one ("Honey Bee," "Never Call Say Goodbye," and "Reach Out, I'll Be There") as one long suite delivered without interrupting the dance beat- a ploy that would become a standard disco format and the basis of house music's energy level.

As the decade progressed, disco music spread far beyond its gay black origins and went on to affect the sound of pop. In its journey from this underground scene, however, disco was whitewashed. The massive success of the 1978 film Saturday Night Fever convinced mainstream America that disco was a new fad),the likes and sound of which had never been seen before. While gay men latched onto the ‘Hi NRG’ Eurodisco beat of Donna Summer's post-‘Love to Love You’ recordings and the camp stylings of Bette Midler.

Indeed, the dance floor proved to be an accurate barometer of the racial differences in the musical tastes of white and black gays and the variation in dancing sensibilities between gay and straight Afro-Americans. Quick to recognize and exploit the profit-making potential of this phenomenon, independent producers began to put out more and more records reflecting a gay black sound.

Starting in 1977, there was an upsurge in the production of disco-like records with a soul, rhythm and blues, and gospel feel: club music was born. The most significant difference between disco and club was rhythm. Club rhythms were more complex and more Africanized. With club music, the gay black subculture reappropriated the disco impulse, as demonstrated by the evolution in disco superstar Sylvester's music.

In 1978 Sylvester had a big hit with "Disco Heat"; in 1980 he released another smash, "Fever." "Disco Heat" was a classic example of the type of disco popular among gay Afro-Americans. At 136 beats per minute it combined the high energy aspect of white gay disco with the orchestral flourishes of contemporary soul. The song also contained the metronomic bass drum that characterized all disco. It was only the gospel and soul-influenced vocals of Sylvester and his back-up singers, Two Tons o’Fun, that distinguished the music from whiter genres of disco.

"Fever," on the other hand, more dearly reflects a black/African sensibility. To begin with, the song starts with the rhythmic beating of cow bells. Sylvester also slowed the beat down to a funkier 116 beats per minute and added polyrhythmic conga and bongo drumming. The drumming is constant throughout the song and is as dominant as any other sound in it. Just as significant, in terms of Africanizing the music, was the removal of the metronomic bass drum that served to beat time in disco. In African music there is no single main beat; the beat emerges from the relation of cross-rhythms and is provided by the listener or dancer, not the musician. By removing the explicit time-keeping bass of disco, Sylvester had reintroduced the African concept of the "hidden rhythm."

While most black pop emphasizes vocals and instrumental sounds, club music tends to place more emphasis on a wide array of percussive sounds (many of which are electronically produced) to create complex patterns of cross-rhythms. In the best of club music, these patterns change very slowly; some remain stable throughout the song. It is this characteristic of club music, above all, that makes it an African-American dance music par excellence. Like disco, club also moved beyond the gay black underground scene. Gay clubs helped spread the music to a "straight" black audience on ostensibly "straight" Friday nights. And some club artists, like Grace Jones, Colonel Abrams, and Gwen Guthrie, achieved limited success in the black pop market.

For most of its history, though, club music largely has been ignored by black-oriented radio stations. Those in New York, for instance, were slow to start playing club music with any regularity; finally WBLS and WRKS began airing dance mixes at various intervals during the day. In the early eighties, the two black-oriented FM radio outlets in Chicago, WBMX and WGCI, began a similar programming format that helped give rise to the most recent variation of gay black music: house.

Pumping Up the Volume

The house scene began, and derived its name from Chicago's now defunct dance club The Warehouse. At the time of its debut in 1977, the club was the only after-hours dance venue in the city, opening at midnight Saturday and closing after the last dancers left on Sunday afternoon. On a typical Saturday night, two to five thousand patrons passed through its doors.

The Warehouse was a small three-story building- literally an abandoned warehouse with a seating area upstairs, free juice, water, and munchies in the basement, and a dimly lit, steamy dance floor in between. You only could reach the dance floor through a trap door from the level above, adding to the underground feeling of the club.

A mixed crowd (predominately gay- male and female) in various stages of undress (with athletic wear and bare flesh predominating) was packed into the dance space, wall to wall. Many actually danced hanging from water pipes that extended on a diagonal from the walls to the ceiling. The heat generated by the dancers would rise to greet you as you descended, confirming your initial impression that you were going down into something very funky and "low."

What set the Warehouse apart from comparable clubs in other cities was its economically democratic admission policy. Its bargain admission price of four dollars made it possible for almost anyone to attend. The Paradise Garage in New York, on the other hand, was a private club that charged a yearly membership fee of seventy-five dollars, plus a door price of eight dollars. The economic barriers in New York clubs resulted in a less "low" crowd and atmosphere, and the scene there was more about who you saw and what you looked like than in Chicago.

For the Warehouse’s opening night in 1977, its owners lured one of New York's hottest DJS, Frankie Knuckles, to spin for the "kids" (as gay Afro-Americans refer to each other). Knuckles found out that these Chicagoans would bring the roof down if the number of beats per minute weren't sky high: "That fast beat [had] been missing for a long time. All the records out of New York the last three years (had] been mid- or down-tempo, and thee kids here in Chicago] won't do that all night long, they need more energy."(3)

Responding to the needs of their audience, the DJs in Chicago's gay black clubs, led by Knuckles, supplied that energy in two ways: by playing club tunes and old Philly songs (like MFSB’s "Love Is the Message") with a faster, boosted rhythm track, and by mixing in the best of up-tempo avant-garde electronic dance music from Europe. Both ploys were well received by the kids in Chicago; the same was not true of the kids in New York.

As Knuckles points out, many of the popular songs in Chicago were big in New York City, "but one of the biggest cult hits, 'Los Ninos' by Liaisons Dangereuses, only got played in the punk clubs there." Dance Music Report noted that for most of the eighties, Chicago has been the most receptive American market for avant-garde dance music. The Windy City's gay black clubs have a penchant for futuristic music, and its black radio stations were the first in the United States to give airplay to Kraftwerk's "Trans Europe Express" and Frankie Goes to Hollywood's "Two Tribes." The Art of Noise, Depeche Mode, David Byrne and the Talking Heads, and Brian Eno were all popular in Chicago's gay black circles.

What's also popular in Chicago is the art of mixing. In an interview with Sheryl Garratt, Farley Keith Williams (a.k.a. "Farley Jackmaster Funk"), one of house music's best known DJ/producers, says: "Chicago is a DJ city .... If there's a hot record out, in Chicago they'll all buy two copies so they can mix it, we have a talent for mixing. When we first started on the radio there weren't many [DJS], but then every kid wanted two turntables and a mixer for Christmas... And if a DJ can't mix, they'll boo him in a minute because half of them probably known [sic] how to do it themselves."

What was fresh about house music in its early days was that folks did it themselves; it was "homemade." Chicago DJs began recording rhythm tracks, using inexpensive synthesizers and drum machines. Very soon, a booming trade developed in records consisting solely of a bassline and drum patterns. As music critic Carol Cooper notes, "basement and home studios sprang up all over Chicago."

DJs were now able to create and record music and then expose it to a dance floor public all their own, completely circumventing the usual process of music production and distribution. These homespun DJs-cum-artists/producers synthesized the best of the avant-garde electronic dance music (Trilogy's "Not Love," Capricorn's "I Need Love," and Telex's "Brain Washed") with the best loved elements of classic African-American dance cuts, and wove it all through the cross-rhythms of the percussion tracks, creating something unique to the character of gay black Chicago.

There are so many variants of house that it is difficult to describe the music in general terms. Still, there are two common traits that hold for all of house: the music is always a brisk 120 bpm or faster; and percussion is everything. Drums and percussion are brought to the fore, and instrumental elements are electronically reproduced. In Western music, rhythm is secondary in emphasis and complexity to harmony and melody. In house music, as in African music, this sensibility is reversed.

Chip E., producer of the stuttering, stripped-down dance tracks "Like This" and "Godfather of House" characterizes house's beat as "a lot of bottom, real heavy kick drum, snappy snare, bright hi-hat and a real driving bassline to keep the groove. Not a lot of lyrics- just a sample of some sort, a melody [just] to remind you of the name of the record."(4).

That's all you can remember- the song's title- if you're working the groove of house music, because house is pure dance music. Don't dismiss the simple chord changes, the echoing percussion lines, and the minimalist melody: in African music the repetition of well-chosen rhythms is crucial to the dynamism of the music. In the classic African Rhythm and African Sensibility, John Chernoff remarks that "repetition continually re-affirms the power of the music by locking that rhythm, and the people listening or dancing to it, into a dynamic and open structure." It is precisely the recycling of well-chosen rhythmic patterns in house that gives the music a hypnotic and powerfully kinetic thrusting, permitting dancers to extract the full tension from the music's beat.

Chernoff argues that the power and dynamic potential of African music is in the gaps between the notes, and that it is there that a creative participant will place his contribution. By focusing on the gaps rather than the beats, the dancers at the Warehouse found much more freedom in terms of dancing possibilities, a freedom that permitted total improvisation.

The result was a style of dancing dubbed "jacking" that more closely resembled the spasmodic up and down movements of people possessed than it did the more choreographed and fluid "vogueing" movement of the dancers at other dubs like New York's Paradise Garage. Dancers at The Warehouse tended to move faster, quirkier, more individualistically, and deliberately off-beat. It's not that the kids had difficulty getting the beat; they simply had decided to move beyond it-around, above, and below it. Dancing on the beat was considered too normal. To dance at the Warehouse was to participate in a type of mass possession: hundreds of young black kids packed into the heat and darkness of an abandoned warehouse in the heart of Chicago during the twilight hours of Sunday morning, jacking as if there would be no tomorrow, It was a dancing orgy of unrivalled intensity, as Frankie Knuckles recalls: "It was absolutely the only club in the city to got to… it wasn't a polished atmosphere - the lighting was real simplistic, but the sound system was intense and it was about what you heard as opposed to what you saw." (5)

No Way Back: House Crosses Over

Like disco and club, house music is rapidly moving beyond the gay black underground scene, thanks in part to a boost from radio play. As early as 1980, Chicago's black-oriented radio stations WBMX and WGCI rotated house music into their programming by airing dance mixes. WBMX signed on a group pf street DJS, the ‘Hot Mix 5’, whose ranks included two of the most prolific and important house producers/artists- Ralph Rosario and Farley Jackmaster Funk. When the Hot Mix crew look to the air on Saturday nights, their five-hour show drew an estimated audience of 250,000 to 1,000,000 Chicagoans.

Now in Chicago, five-year-olds are listening to house and jacking. Rocky Jones, president of the DJ International recording label, points out that ‘[in Chicago, house] appeals to kids, teenagers, blacks, whites, hispanics, straights, gays. When McDonald's HQ throws a party for its employees, they hire house DJs."

Outside of Chicago, house sells mainly in New York, Detroit, D.C., and other large urban/black markets in the Northeast and Midwest. As in Chicago, the music has moved beyond the gay black market and is now very popular in the predominantly white downtown scene in New York, where it regularly is featured in clubs like Boy Bar and the World. But the sound also has travelled uptown, into the boroughs (and even into New Jersey) by way of increased airplay on New York's black radio stations; house can now be heard blasting forth from the boom boxes of b-boys and b-girls throughout the metropolitan area. It has also spread south and west to gay clubs like the Marquette in Atlanta and Catch One in Los Angeles. Even Detroit is manufacturing its own line, tagged "techno-house."

House music has a significant public in England as well, especially in London. In reporting on the house scene in Chicago, the British music press scooped most of its American counterparts (with the notable exception of Dance Music Report) by more than a year. So enthusiastic has been the British response to house that English DJs and musicians (both black and white) are now producing their own variety of house music, known as "acid" house.

House music, however, is not without its critics. Like disco and club, it has been either ignored or libelled by most in the American music press. In a recent Village Voice article hailing the popularity of rap music, Nelson George perfunctorily dismisses the music as "retro-disco." Other detractors of house have labelled the music "repetitive" and "unoriginal." (6)

Because of its complex rhythmic framework, though, house should not be judged by Western music standards but by criteria similar to those used to judge African music. House is retro-disco in the same way and to the same extent that rap is "retro-funk."

The criticism that this music is unoriginal stems from the fact that many house records are actually house versions of rhythms found in old soul and Philly songs. Anyone familiar with African-American musical idioms is aware that the remaking of songs is a time-honored tradition. As John Chernoff has documented, truly original style in African and African-American music often consists in subtle modifications of perfected and strictly respected forms. Thus, Africans remain "curiously" indifferent to what is an important concern of Western culture: the issue of artistic origins.

Each time a DJ plays at a club, it is a different music-making situation. The kids in the club are basically familiar with the music and follow the DJ'S mixing with informed interest. So, when a master DJ flawlessly mixes bits and pieces of classic soul, Philly, disco, and club tunes with the best of more recent house fare to form an evenly pumping groove, or layers the speeches of political heroes (Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, or Jesse Jackson) or funky Americana (a telephone operator's voice or jingles from old television programs) over well known rhythm tracks, the variations stand out clearly to the kids and can make a night at the club a special affair.

To be properly appreciated, house must be experienced in a gay black club. As is true of other African music, it is a mistake "to listen" to house because it is not set apart from its social and cultural context. "You have to go to the clubs and see how people react when they hear it ‘... people jus’ get happy and screamin’”. When house really jacks, it is about the most intense dance music around. Wallflowers beware: you have to move to understand the power of house.

Notes

1. Sheryl Garratt, "Let's Play House," The Face (September 1986), 18-23.

2. lain Chambers, Urban Rhythms: Pop Music and Popular Culture (New York: St. Martin's, 1985), 187-188.

3. Simon Wiffer, "House Music," i-d (September 1986),

4. Garratt, "Let's Play House," 23•

5. Wiffer, "House Music."

6. Nelson George, "Nationwide: America Raps Back," VillageVoice 4,19 January 1988, p.32-33.

Monday, April 21, 2008

Saturday, April 19, 2008

Privatized sound? - from the Walkman to the iPod

I have recently been re-reading some essays written in the 1980s by Marxist/Feminist cultural critic Judith Williamson, collected together in her book Consuming Passions: the Dynamics of Popular Culture (London: Marion Boyars, 1986), The following essay was originally published in the London magazine City Limits in 1983, and is a response to the popularity of the (then new) Sony Walkman personal stereo. 25 years later, with the Walkman superseded by the iPod and music playing mobiles, some of the arguments about their use as amounting to a privatized withdrawal from social life still ring true. But equally part of me feels that human sociability is stronger than any technical device or political offensive to created atomised citizens - with the mobile phone in particular there are contradictory things going on, listening to music in private while simultaneously being involved in communications with others on a scale that would have been unthinkable 25 years ago.

URBAN SPACEMAN

A vodka advertisement in the London underground shows a cartoon man and woman with little headphones over their ears and little cassette-players over their shoulders. One of them holds up a card which asks, 'Your place or mine?' - so incapable are they of communicating in any other way.

The walkman has become a familiar image of modern urban life, creating troops of sleep-walking space-creatures, who seem to feel themselves invisible because they imagine that what they're listening to is inaudible. It rarely is: nothing is more irritating than the gnats' orchestra which so frequently assails the fellow-passenger of an oblivious walk-person sounding, literally, like a flea in your ear. Although disconcertingly insubstantial, this phantom music has all the piercing insistency of a digital watch alarm; it is your request to the headphoned one to turn it down that cannot be heard. The argument that the walkman protects the public from hearing one person's sounds, is back-to-front: it is the walk-person who is protected from the outside world, for whether or not their music is audible they are shut off as if by a spell.

The walkman is a vivid symbol of our time. It provides a concrete image of alienation, suggesting an implicit hostility to, and isolation from, the environment in which it is worn.

Yet it also embodies the underlying values of precisely the society which produces that alienation - those principles which are the lynch-pin of Thatcherite Britain: individualism, privatization and 'choice'. The walkman is primarily a way of escaping from a shared experience or environment. It produces a privatized sound, in the public domain; a weapon of the individual against the communal. It attempts to negate chance: you never know what you are going to hear on a bus or in the streets, but the walk-person is buffered against the unexpected - an apparent triumph of individual control over social spontaneity. Of course, what the walkperson controls is very limited; they can only affect their own environment, and although this may make the individual feel active (or even rebellious) in social terms they are absolutely passive. The wearer of a walkman states that they expect to make no input into the social arena, no speech, no reaction, no intervention. Their own body is the extent of their domain. The turning of desire for control inwards towards the body has been a much more general phenomenon of recent years; as if one's muscles or jogging record were all that one could improve in this world. But while everyone listens to whatever they want within their 'private' domestic space, the peculiarity of the walkman is that it turns the inside of the head into a mobile home rather like the building society image of the couple who, instead of an umbrella, carry a tiled roof over their heads (to protect them against hazards created by the same system that provides their mortgage).

This interpretation of the walkman may seem extreme, but only because first, we have become accustomed to the privatization of social space, and second, we have come to regard sound as secondary to sight - a sort of accompaniment to a life which appears as essentially visual. Imagine people walking round the streets with little TVs strapped in front of their eyes, because they would rather watch a favourite film or programme than see where they were going, and what was going on around them. (It could be argued that this would be too dangerous - but how about the thousands of suicidal cyclists who prefer taped music to their own safety?). This bizarre idea is no more extreme in principle than the walkman. In the visual media there has already been a move from the social setting of the cinema, to the privacy of the TV set in the living-room, and personalized mobile viewing would be the logical next step. In all media, the technology of this century has been directed towards a shift, first from the social to the private - from concert to record-player - and then of the private into the social - exemplified by the walkman, which, paradoxically, allows someone to listen to a recording of a public concert, in public, completely privately.

The contemporary antithesis to the walkman is perhaps the appropriately named ghetto-blaster. Music in the street or played too loud indoors can be extremely anti-social although at least its perpetrators can hear you when you come and tell them to shut up. Yet in its current use, the ghetto-blaster stands for a shared experience, a communal event. Outdoors, ghetto-blasters are seldom used by only their individual owners, but rather act as the focal point for a group, something to gather around. In urban life 'the streets' stand for shared existence, a common understanding, a place that is owned by no-one and used by everyone. The traditional custom of giving people the 'freedom of the city' has a meaning which can be appropriated for ourselves today. There is a kind of freedom about chance encounters, which is why conversations and arguments in buses and bus-queues are often so much livelier than those of the wittiest dinner party. Help is also easy to come by on urban streets, whether with a burst shopping bag or a road accident.

It would be a great romanticization not to admit that all these social places can also hold danger, abuse, violence. But, in both its good and bad aspects, urban space is like the physical medium of society itself. The prevailing ideology sees society as simply a mathematical sum of its individual parts, a collection of private interests. Yet social life demonstrates the transformation of quantity into quality: it has something extra, over and above the characteristics of its members in isolation. That 'something extra' is unpredictable, unfixed, and resides in interaction. It would be a victory for the same forces that have slashed public transport and privatized British Telecom, if the day were to come when everyone walked the street in headphones.

URBAN SPACEMAN

A vodka advertisement in the London underground shows a cartoon man and woman with little headphones over their ears and little cassette-players over their shoulders. One of them holds up a card which asks, 'Your place or mine?' - so incapable are they of communicating in any other way.

The walkman has become a familiar image of modern urban life, creating troops of sleep-walking space-creatures, who seem to feel themselves invisible because they imagine that what they're listening to is inaudible. It rarely is: nothing is more irritating than the gnats' orchestra which so frequently assails the fellow-passenger of an oblivious walk-person sounding, literally, like a flea in your ear. Although disconcertingly insubstantial, this phantom music has all the piercing insistency of a digital watch alarm; it is your request to the headphoned one to turn it down that cannot be heard. The argument that the walkman protects the public from hearing one person's sounds, is back-to-front: it is the walk-person who is protected from the outside world, for whether or not their music is audible they are shut off as if by a spell.

The walkman is a vivid symbol of our time. It provides a concrete image of alienation, suggesting an implicit hostility to, and isolation from, the environment in which it is worn.

Yet it also embodies the underlying values of precisely the society which produces that alienation - those principles which are the lynch-pin of Thatcherite Britain: individualism, privatization and 'choice'. The walkman is primarily a way of escaping from a shared experience or environment. It produces a privatized sound, in the public domain; a weapon of the individual against the communal. It attempts to negate chance: you never know what you are going to hear on a bus or in the streets, but the walk-person is buffered against the unexpected - an apparent triumph of individual control over social spontaneity. Of course, what the walkperson controls is very limited; they can only affect their own environment, and although this may make the individual feel active (or even rebellious) in social terms they are absolutely passive. The wearer of a walkman states that they expect to make no input into the social arena, no speech, no reaction, no intervention. Their own body is the extent of their domain. The turning of desire for control inwards towards the body has been a much more general phenomenon of recent years; as if one's muscles or jogging record were all that one could improve in this world. But while everyone listens to whatever they want within their 'private' domestic space, the peculiarity of the walkman is that it turns the inside of the head into a mobile home rather like the building society image of the couple who, instead of an umbrella, carry a tiled roof over their heads (to protect them against hazards created by the same system that provides their mortgage).

This interpretation of the walkman may seem extreme, but only because first, we have become accustomed to the privatization of social space, and second, we have come to regard sound as secondary to sight - a sort of accompaniment to a life which appears as essentially visual. Imagine people walking round the streets with little TVs strapped in front of their eyes, because they would rather watch a favourite film or programme than see where they were going, and what was going on around them. (It could be argued that this would be too dangerous - but how about the thousands of suicidal cyclists who prefer taped music to their own safety?). This bizarre idea is no more extreme in principle than the walkman. In the visual media there has already been a move from the social setting of the cinema, to the privacy of the TV set in the living-room, and personalized mobile viewing would be the logical next step. In all media, the technology of this century has been directed towards a shift, first from the social to the private - from concert to record-player - and then of the private into the social - exemplified by the walkman, which, paradoxically, allows someone to listen to a recording of a public concert, in public, completely privately.

The contemporary antithesis to the walkman is perhaps the appropriately named ghetto-blaster. Music in the street or played too loud indoors can be extremely anti-social although at least its perpetrators can hear you when you come and tell them to shut up. Yet in its current use, the ghetto-blaster stands for a shared experience, a communal event. Outdoors, ghetto-blasters are seldom used by only their individual owners, but rather act as the focal point for a group, something to gather around. In urban life 'the streets' stand for shared existence, a common understanding, a place that is owned by no-one and used by everyone. The traditional custom of giving people the 'freedom of the city' has a meaning which can be appropriated for ourselves today. There is a kind of freedom about chance encounters, which is why conversations and arguments in buses and bus-queues are often so much livelier than those of the wittiest dinner party. Help is also easy to come by on urban streets, whether with a burst shopping bag or a road accident.

It would be a great romanticization not to admit that all these social places can also hold danger, abuse, violence. But, in both its good and bad aspects, urban space is like the physical medium of society itself. The prevailing ideology sees society as simply a mathematical sum of its individual parts, a collection of private interests. Yet social life demonstrates the transformation of quantity into quality: it has something extra, over and above the characteristics of its members in isolation. That 'something extra' is unpredictable, unfixed, and resides in interaction. It would be a victory for the same forces that have slashed public transport and privatized British Telecom, if the day were to come when everyone walked the street in headphones.

Friday, April 18, 2008

Free Jamyang Kyi

'A Tibetan singer well known as a feminist activist has been taken by Chinese authorities and her family has received no word of her fate. Jamyang Kyi was detained on April 1, friends said. The US government-supporting Radio Free Asia quoted unidentified sources as saying that she had been formally arrested in the western city of Xining. However police made no comment.

Kyi, a longtime producer in the Tibetan-language section of Qinghai Television, the state-run channel for western Qinghai province bordering Tibet, has not been seen since April 7. That was when her husband was last allowed contact with her, friends said' (Times, 17 April 2008). Lots more Tibetan music here.

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

Night Haunts

Sandu suggests that the second world war ‘Blitz did for the London night. It produced life-threatening fear rather than flaneurial frissons’ and that is has been further killed off by ‘a slicked-up form of commodity urbanism… the ‘London night’ has morphed into, and been rebranded as, ‘London nightlife’’.

Night is no longer ‘a distinct, cordoned-off territory in which we may immerse ourselves in strange possibilities or make ourselves susceptible to off-kilter enchantments’. Instead it is a focus of a whole industry: ‘Fun – its conception, manufacture, and promotion – occupies hundreds of thousands of people… Night London is endlessly studied and written about – not for any mysteries it may hold, but because it is now seen as an economic unit… Acronyms clog the pages – TfL, EMZs, the latter standing for Entertainment Management Zones, a new term that describes areas in which large numbers of young people like to hang out in the evening’.

Nevertheless Sandhu still thinks it’s worth his while to explore, hanging out with nocturnal workers and other denizens of the dark – mini-cab drivers, office cleaners, nurses in a sleep clinic and Benedictine nuns at Tyburn Convent praying for the souls of Londoners in a ceremony called the Night Adoration. The image of prayer unites Sandhu’s night-time pilgrims: ‘Listen carefully. People are praying tonight. The blue-light ambulance driver tearing through the streets of South London in the hope that he can still deliver a hit-and-run victim to A&E before it’s too late. The young Chinese vendor who has spent the last few hours ducking in and out of New Cross pubs trying to sell knock-off DVDs, and who now sees a group of toughs looking enviously at his backpack… Prayer is the true language of the night. It is the sound of London’s heart beating. The sound of individuals walking alone in the dark’.

There is something seductive about Sandhu's prose and his argument about the taming of the London night certainly strikes a chord. Still he is well-enough read in Londonist prose to know that there is nothing new about lamenting for the glories of London 's nocturnal past. H.V. Morton, whose The Nights of London (1926) Sandhu takes as a model, mentions that 'Old men who drink port have told me, when warmed up, how beautiful London was at night in those [Victorian] days of side whiskers and plaid trousers and Ouida'.

It also seems to me that in eschewing London 'nightlife' as simply a managed industry, Sandhu has missed out on what is still exciting for many. Nocturnal London isn't just one long dark night of the soul, populated by lonely wanderers whistling in the shadows. There are surely still many making a collective journey on to the dawn and having adventures along the way.

Night, the beloved

'Night, the beloved. Night, when words fade and things come alive. When the destructive analysis of day is done, and all that is truly important becomes whole and sound again'

(Antoine de Saint-Exupery)

image is from a Los Angeles house club called Balance

Saturday, April 12, 2008

Classic party scenes (3): Desperately Seeking Susan

In Susan Seidelman's 1985 film, bored housewife Roberta (Rosanna Arquette) swaps lives with bohemian rock chick/gangster's moll Susan (played by Madonna playing herself), leading Roberta's husband ('the spa king of New Jersey') to seek out Susan to help him find his wiife. 'Meet me at 30 West 21st Street' says Susan/Madonna and so the hapless yuppie finds himself dancing to 'Get Into the Groove' surrounded by an assortment of post-punk/new romantic haircuts. Earlier in the film, by way of contrast, we've seen his own tedious house party - a few nibbles, no dancing, conversations with dentists. Out on the dancefloor he really lets go, well loosens his tie anyway - 'only when I'm dancing can I feel this free'.

The scene was shot in real New York club Danceteria (fondly remembered here before by Charles Donelan), with various regulars and staff from the club in the film scene.

Tuesday, April 01, 2008

Mexico 'Emo' Bashing

Last week in Lancashire a 15 -year-old was convicted to 'stamping to death a young woman in a park because she was dressed as a Goth'.

Now from Mexico and Chile comes news of a wave anti-emo attacks. According to NME: "On March 7 around 800 young people in the city of Querataro amassed against emos in the city resulting in many violent attacks, and a week later a similar incident occurred in Mexico City. Emos in both cities responded to the attacks by marching peacefully through the center of the cities. Meanwhile, Chile is also seeing a wave of violence against emo, with TV station Chilevision showing an attack on a group of PokEMOns by skinheads. Emo’s in Chile are known as PokEMOns in different parts of the country."

As usual in incidents like these, sexuality is at the heart of the matter with so-called emos being targeted for dressing effeminately and wearing make up: "At the core of this is the homophobic issue. The other arguments are just window dressing for that," said Victor Mendoza, a youth worker in Mexico City. "This is not a battle between music styles at all. It is the conservative side of Mexican society fighting against something different."

Now from Mexico and Chile comes news of a wave anti-emo attacks. According to NME: "On March 7 around 800 young people in the city of Querataro amassed against emos in the city resulting in many violent attacks, and a week later a similar incident occurred in Mexico City. Emos in both cities responded to the attacks by marching peacefully through the center of the cities. Meanwhile, Chile is also seeing a wave of violence against emo, with TV station Chilevision showing an attack on a group of PokEMOns by skinheads. Emo’s in Chile are known as PokEMOns in different parts of the country."

As usual in incidents like these, sexuality is at the heart of the matter with so-called emos being targeted for dressing effeminately and wearing make up: "At the core of this is the homophobic issue. The other arguments are just window dressing for that," said Victor Mendoza, a youth worker in Mexico City. "This is not a battle between music styles at all. It is the conservative side of Mexican society fighting against something different."

Saturday, March 29, 2008

Turnmills closes

Another London nighttime landmark has closed, following the final weekend of Turmills - the famous club in Clerkenwell. The final record to be played last Monday afternoon was apparently Blue Monday by New Order. Landlord Derwent London is planning to convert the building into an office block.

Another London nighttime landmark has closed, following the final weekend of Turmills - the famous club in Clerkenwell. The final record to be played last Monday afternoon was apparently Blue Monday by New Order. Landlord Derwent London is planning to convert the building into an office block.Turnmills opened as a wine bar in 1985 and came into its own as a club from 1990 when it became the first in the country to be granted a licence to open 24 hours a day all year round. In the mid-1990s it became home to groundbreaking gay nights Trade and FF and then to the Friday house night The Gallery, which started in July 1994 and featured DJ 'Tall' Paul Newman - whose dad John Newman owned the club.

I spent some happy nights at The Gallery and techno club Eurobeat 2000 which was also held there for a while. The pages reproduced here are a hyperbolic article about The Gallery from Muzik magazine (July 1998 - click on them to read) which described it as 'the full-on Northern club night in the middle of London' on the basis of it being an attitude-free night of full-on hedonism in 'a cool venue full of twists, turns and little hideways to indulge in a "bit of the other"'. It is true that the dancefloor wasn't massive, but it didn't matter as there were speakers all over the place and people danced wherever they happen to be standing, by the bar or the pinball machine as well as on the dancefloor proper.

There was also a gallery overlooking the main part of the club. I remember sitting up there on The Gallery's first birthday night in 1995, watching Boy George (who is a tall bloke) walking though the crowd in a T-shirt saying "Hate is not my drug", shaking hands, and heading into the DJ booth to announce himself with Lippy Lou's Liberation, followed by a stampede to the dance floor. I remember wearing a silver sparkly top, girls with fairy wings and a man walking into the toilets wearing a dress and offering round a bowl of bonbons (at Easter 1996 they also gave out chocolate mini eggs at the door). Musically I remember pumped up mixes of disco classics I Feel Love and Do you wanna Funk, Insomnia by Faithless and more than anything else bouncing around under the lasers to Access by DJ Misjah & Tim.

In his book, London: The Biography, Peter Ackroyd mentions Turnmills, seeing it as an inheritor of Clerkenwell's historic reputation for disrespectful nightlife and more broadly as 'the harbour for the outcast and those who wished to go beyond the law'. For Ackroyd, these continuities in London life 'suggest that there are certain kinds of activity, or patterns of inheritance, arising from the streets and alleys themselves', a kind of spirit of place which he has referred to as a 'territorial imperative'. Whether this spirit of Clerkenwell will withstand property developers remains to be seen. Derwent London at least seem intent on exorcising the ghosts of Clerkenwell radical and salubrious past, stating that their business is 'to improve the desirability of people coming to these buildings'.

Saturday, March 22, 2008

Here We Dance

Last week I went to the launch of Here We Dance, at Tate Modern. The exhibition aims to look at 'the relationship between the body and the state, exploring how the physical presence and circulation of bodies in public space informs our perceptions of identity, nation, society and democracy. The title derives from a work by Ian Hamilton Finlay, which refers to the celebrations that took place during the French Revolution, and alludes to the importance of social gathering in any form of political action or resistance. Bodily movements and gestures, collective actions and games are examined through media as diverse as film, photography, neon text and performance'.

At the private view there was a performance of Gail Pickering's Zulu - a woman moving around wooden shapes while reciting texts which seemed to be from the Weather Underground and similar 60s/70s urban guerrilla groups. This is powerful material that needs a lot of critical discussion and I am not convinced that playing with it in a gallery context really allows the space for reflection - given that most people viewing it would have no idea of the context or even where these words come from.

For me, the most striking piece is the late Ian Hamilton Finlay’s neon sign Ici on Danse ('here we dance/here one dances') - the words displayed at the entrance to a festival that was held on the site of the Bastille in July 1790 to celebrate the anniversary of the storming of the prison. On the gallery wall next to the sign, there is an accompanying text by Camille Desmoulins:

‘While the spectators, who imagined themselves in the gardens on Alcinous, were unable to tear themselves away, the site of the Bastille and its dungeons, which had been converted into groves, held other charms for those whom the passage of a single year had not yet accustomed to believe their eyes. An artificial wood, consisting of large trees, had been planted there. It was extremely well lit. In the middle of this lair of despotism there had been planted a pike with a cap of liberty stuck on top. Close by had been buried the ruins of the Bastille. Amongst its irons and gratings could be seen the bas-relief representing slaves in chains which had aptly adorned the fortress’s great clock, the most surprising aspect of the sight perhaps being that the fortress could have been toppled without overwhelming in its fall the posterity of the tyrants by whom it had been raised and who had filled it with so many innocent victims. These ruins and the memories they called up were in singular contrast with the inscription that could be read at the entrance to the grove – a simple inscription whose placement gave it a truly sublime beauty – ici on danse’.

The image of dancing on the ruins of the Bastille certainly appeals to me, even if the experience of Desmoulins – a revolutionary executed in 1794 by the new post-revolutinary authorities – suggests that those celebrating should always be looking over their shoulder for those building new Bastilles around the corner.

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

Neither Washington, nor Moscow, but Eton?

Interesting article by John Harris in today's Guardian looking at the seemingly bizarre phenomenon of English Conservative politicians expressing their love for the anti-Conservative music of their 1980s youth. That Tory leader David Cameron claims to like The Smiths, Billy Bragg and The Jam is not new - the latter particularly amusing as Cameron went to top toff public school Eton, satirised by The Jam in a song that included the line 'Hello, hooray, I'd prefer the plague/To the Eton rifles'. Paul Weller of The Jam at least remains uncompromising about this period according to Harris: "I think they were absolute fucking scum - especially Thatcher, who I think should be shot as a traitor to the people. I still think that, and nothing will ever change my opinion. We're still feeling the effects of what they did to the country now, and probably always will: the whole breakdown of communities, trade unions, the working class - the dismantling of lots of things."

More surprizing was to hear that Conservative MP Ed Vaizey was a fan of avowed trotskyists The Redskins: 'he still treasures a vinyl copy of their sole album Neither Washington Nor Moscow - strap-lined, in keeping with a Socialist Workers party slogan, "but international socialism"'.

The article mentions a day that I remember well: "Bragg has a theory that when he, The Smiths and the Redskins played a benefit for the doomed GLC in 1986, Cameron was probably in the audience". The gig in question was actually the Greater London Council-sponsored 'Jobs for a Change' festival on 10th June 1984, in Jubilee Gardens on London's South Bank. The GLC, then controlled by the Labour Left, was in the process of being abolished by the right-wing Thatcher government. Whatever the limitations of municipal labourism, the GLC did put on some fantastic free festivals in this period. As well as this one with The Smiths, I also saw The Pogues at an event in Battersea Park (1985) and The Damned, The Fall. New Model Army and Spear of Destiny in Brockwell Park, Brixton (1984). These were huge events, 80,000+ plus.

I could hardly forget seeing The Smiths but what sticks in my mind from that time is a feeling of powerlessness not of collective strength. While The Redskins were playing, a group of fascist skinheads stormed the stage. Despite there being thousands of avowed leftists in the crowd and only a few dozen nazis (at most), the former mostly fled in panic. Shortly afterwards a group of anti-fascists punks, Class War and Red Action types found each other and chased the fascists through the crowd - only to be slagged off by other festival-goers for being aggressive and spoiling their party. Later I saw the skinheads returning towards the festival over Waterloo Bridge - when I tried to summon up some interest from stewards I was met with complete indifference. After all these people had only just physically attacked one of the bands playing, nothing to worry about!

In the light of this I would have to reluctantly agree - albeit from a diametrically opposed perspective - with Tory MP Vaizey who is quoted in the Guardian article saying: "People could do all this ranting from the stage, but you knew it wasn't going to change the tide of history."

There are some interesting considerations in this whole discussion about the limitations of pop politics, and despite my loathing of Conservative appropriation of music that I love, I would also question any suggestion that people should automatically let their taste in music determine their political perspective, even if the bands' political perspective is a good one - that way lies the aestheticization of politics and the abandoment of critical thinking.

There is a recording of The Smiths GLC set out there somewhere

More surprizing was to hear that Conservative MP Ed Vaizey was a fan of avowed trotskyists The Redskins: 'he still treasures a vinyl copy of their sole album Neither Washington Nor Moscow - strap-lined, in keeping with a Socialist Workers party slogan, "but international socialism"'.

The article mentions a day that I remember well: "Bragg has a theory that when he, The Smiths and the Redskins played a benefit for the doomed GLC in 1986, Cameron was probably in the audience". The gig in question was actually the Greater London Council-sponsored 'Jobs for a Change' festival on 10th June 1984, in Jubilee Gardens on London's South Bank. The GLC, then controlled by the Labour Left, was in the process of being abolished by the right-wing Thatcher government. Whatever the limitations of municipal labourism, the GLC did put on some fantastic free festivals in this period. As well as this one with The Smiths, I also saw The Pogues at an event in Battersea Park (1985) and The Damned, The Fall. New Model Army and Spear of Destiny in Brockwell Park, Brixton (1984). These were huge events, 80,000+ plus.

I could hardly forget seeing The Smiths but what sticks in my mind from that time is a feeling of powerlessness not of collective strength. While The Redskins were playing, a group of fascist skinheads stormed the stage. Despite there being thousands of avowed leftists in the crowd and only a few dozen nazis (at most), the former mostly fled in panic. Shortly afterwards a group of anti-fascists punks, Class War and Red Action types found each other and chased the fascists through the crowd - only to be slagged off by other festival-goers for being aggressive and spoiling their party. Later I saw the skinheads returning towards the festival over Waterloo Bridge - when I tried to summon up some interest from stewards I was met with complete indifference. After all these people had only just physically attacked one of the bands playing, nothing to worry about!

In the light of this I would have to reluctantly agree - albeit from a diametrically opposed perspective - with Tory MP Vaizey who is quoted in the Guardian article saying: "People could do all this ranting from the stage, but you knew it wasn't going to change the tide of history."

There are some interesting considerations in this whole discussion about the limitations of pop politics, and despite my loathing of Conservative appropriation of music that I love, I would also question any suggestion that people should automatically let their taste in music determine their political perspective, even if the bands' political perspective is a good one - that way lies the aestheticization of politics and the abandoment of critical thinking.

There is a recording of The Smiths GLC set out there somewhere

Wednesday, March 05, 2008

Classic party scenes (2): Basic Instinct

It's 1992 and cop Michael Douglas pursues suspect psycho Sharon Stone into a San Francisco club with sex, drugs and pumping sounds by Channel X (Rave the Rhythm) and LaTour (Blue). Jacques Peretti once characterised this as 'The Citizen Kane of club scenes... in which Michael Douglas, playing an Andrew Neil-lookalike in V-neck jumper and no shirt (a sweaty fashion detail signifying middle-aged man smelling out sex) watches Sharon Stone, who taunts his manhood by indulging in a faux-lesbian sex dance'.

Apparently this scene was not filmed in a real club but on a Hollywood film set inspired by the Limelight Club in New York.

Sunday, February 24, 2008

Trance Dancing

I originally wrote this article for ‘Head’ magazine where it was published in issue no.10, ‘Altered States’, 2000.

After more than ten years of the instant altered states offered by drugs, dancing and electronic beats it has become almost a cliche for people to see themselves as following the shaman’s footsteps on the dancing ground. A typical example talks of 'techno trance parties as the new contemporary ritual', embodying “the power of ecstatic trance dancing' like 'the temple dancers of Egypt, the ecstatic Dionysian dances in the temples of Greece', Sufis, Native American Sundancers and Australian Aboriginals (Return to the Source).

Music, dance (and sometimes pyshcoactive plants) are certainly key ‘archaic techiques of ecstasy’ (Eliade) used to achieve trance states throughout history and in most parts of the world. But it is misleading to think of a universal, unchanging trance dance. There is a great deal of variation in terms of the kind of music used (and in some cases there is even dancing without music); the bodily movements of the dance, which range from the calm to the frenetic; and the kind of mental state induced. Most importantly, the meaning given to the trance state varies according to the ritual context and the beliefs of the participants.

Clearly there are parallels with modern dance scenes, but it is arrogant to assume that all the various techniques of trance dancing amount to the same thing as staying up all night at a club in South London. It implies that we already know it all, and have nothing more to learn. Considering the differences may be more instructive.

In most settings, trance dance is not just about hedonism (although pleasure is often part of it) or even the mystical state of oneness. Typically, trance involves some notion of possession, with spirits being invoked in a controlled ritual context. These spirits may be ancestors, nature sprites or aspects of Gods and Goddesses. Furthermore these rituals tend to be undertaken not just to achieve altered states of consciousness but to bring about change in the material world, such as curing sickness or making it rain. These rituals can be very complex, with the trance dance only one element. For instance the all night dance of the Navajo’s healing ‘medicine sing’ marked the conclusion of a nine-day ceremonial featuring prayers, sand paintings, sweat baths and medications.

It follows from this complexity that to be able to master the trance experience can take years of training. It is perhaps typical of the commodified New Age spiritual supermarket that people imagine they can achieve the same results for the price of a pill and a ticket.

To say that contemporary mass dancing offers a different kind of trance experience is not to say that it is always inferior. Practitioners of esoteric/magical trance dancing sometimes bemoan the lack of focus for the energy raised in a club or party, but in some ways the key to this experience is precisely the pleasure of abandon and excess without purpose, an anti-economic expenditure of energy without return (Bataille).

There is a clear political aspect to many traditional trance practices. I.M. Lewis refers to spirit possession/trance as a ‘ strategy of mystical attack’ by which people of low social status are able to act and speak in ways which would not otherwise be socially permitted. He gives examples of spirits which possess women and servants, demanding that their husbands or masters treat them with respect or offer them gifts. Since it is the gods or the sprits who are responsible, this ritualised rebellion is tolerated within certain limits, beyond which people risk being labelled as witches or sorcerers.

Trance dancing is also characterised by what the anthropologist Victor Turner calls ‘liminality’ (from the Latin for threshold). This describes the way that people in ritual activity ‘separate themselves... from the roles and statuses they have in the workaday world’ crossing the threshold to a space emphasising ‘equality, anonymity and foolishness when compared with the heterogeneous, status-marked, name-conscious intelligence of the social order’ (Driver).

An example is the medieval phenomenen known as St Vitus Dance or tarantism. In Germany, Holland, Belgium and Italy ‘In times of misery, the most abused members of society felt themselves seized by an irresistable urge to dance wildly until they reached a state of trance and collapsed exhausted... peasants left their ploughs, mechanics their workshops, house-wives their domestic duties, children their parents, servants, their masters - all swept headlong into the Bacchanialian revelry’ (Lewis).

Trance dancing ceremonies often involve reaffirming the bonds between people, between the living and the ancestral dead; between humans, animals and the land. Turner calls this ‘communitas’, a spirit of unity and mutual belonging generated by ritual that is more than simply the fact of living in a common space implied by ‘community’.

Prior to their last stand against confinement in a reservation in the 1870s, the Comanches held an elaborate sun dance: ‘the people danced in bands for five days before the sun dancers themselves danced, drummed and sang for three further days, doing without food and water for the duration of the dance’ (Wilson). We can trace a similar link between dance, community and resistance today. On Reclaim the Streets parties for instance dance music is much more than just a soundtrack. It is the act of dancing together that help creates a collectivity from a collection of isolated individuals, giving us a sense of our power and a vision of a different way of being.

Anybody who has been out dancing in the last ten years will recognise something of their own experience in these ideas of liminality and communitas. (I would add that this applies not just in the self-defined trance scene, but in dance music scenes generally whatever the soundtrack.). Of course, it is possible to criticise this experience as illusory, compensating for, but not challenging the ruling society that denies real community. In this sense, the contemporary dance scene could be said to perform the same role as religion as ‘the heart of heartless world... the opiate of the masses’ (Marx). And there is a truth in this. In clubs you sometimes get an incredible mix of people dancing together, but whatever the feeling of togetherness, at the end of the night some go back to stately homes, some to children’s homes. Yet, however fleeting this feeling, it is never entirely a fiction - even if it only provides a glimpse of how different things could be.

References:

- G. Bataille, Eroticism, 1962.

- T.F. Driver, The magic of ritual: our need for liberating rites that transform our lives and our communities, 1991.

- M. Eliade, Shamanism: archaic techniques of Ecstasy.

- I.M. Lewis, Ecstatic Religion: an anthropological study of spirit possession and shamanism.

- Return to the Source, Deep Trance and Ritual Beats booklet, 1995

- B. Wilson, Magic and the Millenium, 1973.

After more than ten years of the instant altered states offered by drugs, dancing and electronic beats it has become almost a cliche for people to see themselves as following the shaman’s footsteps on the dancing ground. A typical example talks of 'techno trance parties as the new contemporary ritual', embodying “the power of ecstatic trance dancing' like 'the temple dancers of Egypt, the ecstatic Dionysian dances in the temples of Greece', Sufis, Native American Sundancers and Australian Aboriginals (Return to the Source).

Music, dance (and sometimes pyshcoactive plants) are certainly key ‘archaic techiques of ecstasy’ (Eliade) used to achieve trance states throughout history and in most parts of the world. But it is misleading to think of a universal, unchanging trance dance. There is a great deal of variation in terms of the kind of music used (and in some cases there is even dancing without music); the bodily movements of the dance, which range from the calm to the frenetic; and the kind of mental state induced. Most importantly, the meaning given to the trance state varies according to the ritual context and the beliefs of the participants.

Clearly there are parallels with modern dance scenes, but it is arrogant to assume that all the various techniques of trance dancing amount to the same thing as staying up all night at a club in South London. It implies that we already know it all, and have nothing more to learn. Considering the differences may be more instructive.

In most settings, trance dance is not just about hedonism (although pleasure is often part of it) or even the mystical state of oneness. Typically, trance involves some notion of possession, with spirits being invoked in a controlled ritual context. These spirits may be ancestors, nature sprites or aspects of Gods and Goddesses. Furthermore these rituals tend to be undertaken not just to achieve altered states of consciousness but to bring about change in the material world, such as curing sickness or making it rain. These rituals can be very complex, with the trance dance only one element. For instance the all night dance of the Navajo’s healing ‘medicine sing’ marked the conclusion of a nine-day ceremonial featuring prayers, sand paintings, sweat baths and medications.

It follows from this complexity that to be able to master the trance experience can take years of training. It is perhaps typical of the commodified New Age spiritual supermarket that people imagine they can achieve the same results for the price of a pill and a ticket.

To say that contemporary mass dancing offers a different kind of trance experience is not to say that it is always inferior. Practitioners of esoteric/magical trance dancing sometimes bemoan the lack of focus for the energy raised in a club or party, but in some ways the key to this experience is precisely the pleasure of abandon and excess without purpose, an anti-economic expenditure of energy without return (Bataille).

There is a clear political aspect to many traditional trance practices. I.M. Lewis refers to spirit possession/trance as a ‘ strategy of mystical attack’ by which people of low social status are able to act and speak in ways which would not otherwise be socially permitted. He gives examples of spirits which possess women and servants, demanding that their husbands or masters treat them with respect or offer them gifts. Since it is the gods or the sprits who are responsible, this ritualised rebellion is tolerated within certain limits, beyond which people risk being labelled as witches or sorcerers.

Trance dancing is also characterised by what the anthropologist Victor Turner calls ‘liminality’ (from the Latin for threshold). This describes the way that people in ritual activity ‘separate themselves... from the roles and statuses they have in the workaday world’ crossing the threshold to a space emphasising ‘equality, anonymity and foolishness when compared with the heterogeneous, status-marked, name-conscious intelligence of the social order’ (Driver).

An example is the medieval phenomenen known as St Vitus Dance or tarantism. In Germany, Holland, Belgium and Italy ‘In times of misery, the most abused members of society felt themselves seized by an irresistable urge to dance wildly until they reached a state of trance and collapsed exhausted... peasants left their ploughs, mechanics their workshops, house-wives their domestic duties, children their parents, servants, their masters - all swept headlong into the Bacchanialian revelry’ (Lewis).

Trance dancing ceremonies often involve reaffirming the bonds between people, between the living and the ancestral dead; between humans, animals and the land. Turner calls this ‘communitas’, a spirit of unity and mutual belonging generated by ritual that is more than simply the fact of living in a common space implied by ‘community’.

Prior to their last stand against confinement in a reservation in the 1870s, the Comanches held an elaborate sun dance: ‘the people danced in bands for five days before the sun dancers themselves danced, drummed and sang for three further days, doing without food and water for the duration of the dance’ (Wilson). We can trace a similar link between dance, community and resistance today. On Reclaim the Streets parties for instance dance music is much more than just a soundtrack. It is the act of dancing together that help creates a collectivity from a collection of isolated individuals, giving us a sense of our power and a vision of a different way of being.

Anybody who has been out dancing in the last ten years will recognise something of their own experience in these ideas of liminality and communitas. (I would add that this applies not just in the self-defined trance scene, but in dance music scenes generally whatever the soundtrack.). Of course, it is possible to criticise this experience as illusory, compensating for, but not challenging the ruling society that denies real community. In this sense, the contemporary dance scene could be said to perform the same role as religion as ‘the heart of heartless world... the opiate of the masses’ (Marx). And there is a truth in this. In clubs you sometimes get an incredible mix of people dancing together, but whatever the feeling of togetherness, at the end of the night some go back to stately homes, some to children’s homes. Yet, however fleeting this feeling, it is never entirely a fiction - even if it only provides a glimpse of how different things could be.

References:

- G. Bataille, Eroticism, 1962.

- T.F. Driver, The magic of ritual: our need for liberating rites that transform our lives and our communities, 1991.

- M. Eliade, Shamanism: archaic techniques of Ecstasy.

- I.M. Lewis, Ecstatic Religion: an anthropological study of spirit possession and shamanism.

- Return to the Source, Deep Trance and Ritual Beats booklet, 1995

- B. Wilson, Magic and the Millenium, 1973.

Wednesday, February 06, 2008

Clubbing in Luton 1983-87

In the mid-1980s the centre of the musical universe, or at least my universe at that time was Luton in Bedfordshire. For any non-UK readers, this is an industrial town 30 miles north of London – or at least it was at this point, before General Motors closed down the Vauxhall car factory.

Martin at Beyond the Implode has chronicled his memories of the downside of living there in the early 1990s – driving around all night listening to Joy Division on the run from ‘Clubs where you'd pay 10 quid to enter (5 if you were a girl) with the promise of a free bar all night. Pints of watered down Kilkenny Ajax, or single vodkas with a squirt of orange. Bobby Brown skipping on the club's CD-player. Bare knuckle boxing tournaments outside kebab shops’. Sarfraz Manzoor has also painted a less than flattering account of the town in his book Greetings from Bury Park: Race, Religion, Rock’n’Roll (later filmed as Blinded by the Light).

There’s nothing in these accounts I would really disagree with, though only people who have lived in Luton earn the right to criticise it. I would of course defend it against other detractors by pointing out to its interesting counter-cultural history!

I was born and grew up in Luton and give or take some time away at college I stayed there until my mid-20s, spending my last few years in the town as a pretty much full time anarcho-punk. I think the anarcho-punk stories can wait until another post, but for now lets look at the mid-1980s nightlife, such as it was.

The Blockers Arms

There were several pubs with an ‘alternative’ crowd in Luton around this time – The Black Horse, The Sugar Loaf, later the Bricklayers Arms. But in the mid-1980s the various sub-cultures of punks, psychobillies, skinheads and bikers tended to congregate at one pub more than any other, The Blockers Arms in High Town Road. A hostile local historian has written that ‘During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the pub became a Mecca for some of the undesirable elements of Luton society, it being reported that the pub was used by drug-peddlers, with the result that there was much trouble with fights and under-age drinking’ (Stuart Smith, Pubs and Pints: the story of Luton’s Public Houses and Breweries, Dunstable: Book Castle, 1995). Most of this is true, but of course we all thought we were very desirable!

The micro-tribes gathered in the pub were united in their alienation from mainstream Luton nightlife, whilst suspicious of each other, sometimes to the point of violence. The bikers dominated the pool table and the dealing. The traditional charity bottle on the bar read ‘support your local Hells Angels’, and you really didn’t want to argue with them. Skinheads would turn up looking for a fight, throwing around glasses. Even among the punks there were different factions, albeit overlapping and coexisting peacefully – some slightly older first generation punks, Crass-influenced anarcho-punks and goths. There were the early indie pop kids too, though I don't think anybody called them that at the time (The Razorcuts came from Luton as did Talulah Gosh's Elizabeth Price). The layout of the pub catered for the various cliques as there were different areas – the inside of the pub had little booths (the smallest for the DJ), and there was also an outside courtyard where bands sometimes played. I remember for instance seeing Welwyn's finest The Astronauts there, as well as Luton punk bands such as Karma Sutra and The Rattlesnakes.

I saw in 1984 in the Blockers. There was drinking, singing and dancing, with midnight marked with Auld Lang Syne and U2’s ‘New Year’s Day’. Inevitably Bowie’s 1984 also got an airing. Later in the year it closed down for refurbishment in the latest of a series of doomed attempts to lose its clientele. It reopened only to lose its license in 1986, closing soon after. The pub later reopened and eventually became The Well.

Sweatshop parties

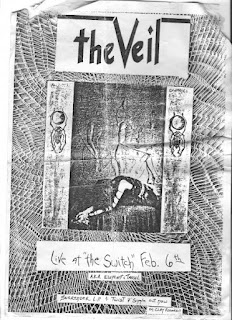

After The Blockers on that New Year’s Eve nearly everybody went on to a warehouse party at 'the Sweatshop' (22a Guildford Street). Luton had once been famous for its hat industry – blockers were one of the groups of workers involved – and there were various former hat factory spaces in the old town centre. One of these was put into action on Christmas Eve 1983 and again on New Year’s Eve – the flyer for the former being recycled for the latter, inviting people to bring their own bottle and dance till dawn for £1. As well as Cramps, Siouxsie and the Banshees etc. there was lots of 1950s music, in addition to what I noted in my diary at the time as drinking, dancing, kissing and falling around. The flyer states 'Dirt Box Rip Off', a reference to the popular Dirt Box warehouse parties in London at that time.

The space was used a few times in the mid-80s for parties over Christmas and New Year. There was a small room downstairs and a big open space upstairs, I remember one time the banister on the staircase between the two collapsed, and somebody broke their arm. But most people there would surely rather have taken their chances with dodgy health and safety than risked going out in the main clubs and bars of Luton town centre.

I did occasionally go there on Tuesdays, when with punters in short supply free tickets were given out to more or less anybody able to buy a drink – seemingly regardless of age as well as clothes. The music was whatever was in the charts with a DJ who spoke over the records mixing sexist banter with comments designed to police the dancefloor – telling my friends to stop their raucous slam dancing with the warning ‘do you girls want to stay until one o’clock?’ (not sure they did actually).

For one night only in 1984, the Tropicana Beach fell into the hands of the freaks. The local TV station BBC East were filming a performance by Furyo, one of the splinters from the break up of Luton’s main punk band, UK Decay, and all the local punks, goths and weirdoes were rounded up to be the audience.

Another occasional oasis was Luton’s only gay club, Shades in Bute Street (formerly the Pan Club). In 1983 it hosted Club for Heroes, an attempt at a new romanticish club night with lots of Bowie, Kraftwerk and Iggy Pop. I particularly remember Yello’s ‘I love you’ playing there. There were attempts at robotic dancing -whenever I hear the Arctic Monkeys sing of 'dancing to electro-pop like a robot from 1984' I am transported back to this place. All this for £1 and beer at 82p a pint!

I remember going too to this night at the Unigate Club on Leagrave Road in 1983 (I think). Occult Radio present The Pits, Click Click and World Circus. I believe the latter featured Gaynor,former lead singer with Luton punk band Pneumania.