I enjoyed 'Blinded by The Light', Gurinder Chadha's movie based on Sarfraz Manzoor’s ‘Greetings from Bury Park: Race, Religion, Rock'n'Roll’ - his book about growing up in a British Pakistani family in Luton in the 1980s and finding solace in the music of Bruce Springsteen. In some ways it’s a feel good jukebox movie with characters bursting into song or reciting Springsteen lyrics at any moment- well if the ABBA oeuvre can be transplanted from Sweden to a Greek Island (Mama Mia) why not Springsteen in Luton? Indeed a key point of the film is that Springsteen’s apparent Americana deals with universal themes and that in Luton like New Jersey people are struggling to find the promised land amidst closing factories, despair and dreams deferred.

Personally it’s impossible to be objective as I too grew up in Luton in this period, albeit a few years older, and when you ‘come from cities you never see on the screen’ (or large industrial towns in this case) there is some excitement at just being represented. So of course I spotted local scenes like George Street (the high street) and the Arndale Centre, including the upstairs cafe where IIRC now-Bristol Labour MP Kerry McCarthy once worked a Saturday job. And I bemoaned the scenes filmed elsewhere: Luton Sixth Form College, which I also attended, is a key location but a school in London was used to stand in for it here- maybe because the actual Sixth Form has been rebuilt since the 80s.

But the film is not just some niche 1980s nostalgia trip - there is darkness on the edge, and indeed in the centre of this town like many others. The personal story of teenage romance, family conflict and fandom is played out against a background of the social tensions of the time - in particular unemployment and racism. In case anyone thinks this is exaggerated, here's some of my own memories and some documentation.

Job cuts at Vauxhall

Luton was synonymous with General Motors at this time, as home to factories making Vauxhall cars and Bedford vans. It wasn't just the major employer, but a big part of community life with its sports grounds and social activities. I remember as a kid going on Vauxhall trips to the pantomime, and learning judo for a while in the sports centre. But this was beginning to change in the 1980s as thousands of workers - like the father in the film - were laid off.

1981 started with the announcement of mass job losses and short time working at Vauxhall Motors, and a further 2000 redundancies came in July 1981 (Luton News, 16/7/81) followed by 200 more in the engineering department later in the year. The latter prompting a walk out and 1000-strong demonstration to present the managing director with a coffin marked ‘RIP Vauxhall design’ (‘Vauxhall job cuts spark mass demo’, Luton News, 12/11/81).

Jobs continued to go throughout the decade. In a few months in 1986, GM cut more than 4,000 jobs at its plants in Luton, Dunstable and Ellesmere Port in Liverpool, leading to Manzoor's dad being made redundant after working for the firm for 15 years.

|

| 'Body Blow to Bedford: shock as GM job toll hits 4150 since June', TASS (union) News and Journal, October 1986 |

My dad worked for Vauxhall in Luton too, as a draughtsman in the design and engineering AJ Block. In 1988 GM sold off this part of the company to another firm- David J B Brown. I remember my dad being involved in organising demonstrations like those pictured below against the threat of losing their Vauxhall pensions and other changes to their working conditions.

|

| Demonstration at Vauxhall in Luton against sell off of design and engineering, 1988 |

Racism in Luton

In his book Manzoor describes the casual racism of some teachers and pupils at his Luton school (Lea Manor) and having to change his route to avoid skinheads hanging out in the subway on Marsh Farm estate. He also refers to the opening of the first purpose built Mosque in Luton, which was marred by racists placing a pig's head on the minaret during the first week (this occurred in 1982). As a young white man I obviously had a very different experience of racism but I was certainly aware of it and involved in local anti-racist politics.

I've written here previously about taking part in anti-National Front protests in Luton in 1979/80, but the heaviest year was 1981.

Then and now, the area of Luton with the highest concentration of South Asian people was Bury Park, an area of terraced housing clustered around Dunstable Road about half a mile from the town centre. The area is also home to Luton Town Football Club's Kenilworth Road ground, and on Boxing Day in December 1980 the mighty Hatters beat Chelsea 2-0. The latter's supporters included a vocal far right element and at 1.30 pm, after the match had finished, 150 - 200 Chelsea fans gathered outside the nearby Mosque in Westbourne Road, where women were praying. The Chelsea fans began kicking at the door, and when Muslim men came outside they were met with a hail of bricks. Four people were injured and £2000 of damage caused to the Mosque.

The police not only failed to prevent the attack, but went on to downplay its obviously racist nature. Mr Akbar Khan of the Pakistani Welfare Association told the Luton News (31/12/1980): 'The police say they cannot do anything because this was just football hooliganism. But it was nothing to do with football, it was purely a racist attack'.

On Saturday 3rd January 1981, I took part in a small Anti-Nazi League march to the Mosque where we joined with local Muslims to guard it against any further attack (Luton were again playing at home). The following day 500 people attended a community meeting at Beech Hill School, attended by the Pakistani Ambassador, local councillors and Ivor Clemitson, former Luton Labour MP and chair of the Community Relations Council. The meeting demanded a public enquiry into police conduct on the day of the attack on the mosque.

Over the next few months, racist attacks continued in the town. For instance on 9 April 1981 racist graffiti was painted on Asian shops and property in Leagrave Road and Marsh Road, Luton. Slogans included 'W*gs', 'P*kis go Home' and National Front symbols (Luton News, 3.9.1981)

The Luton Youth Movement

In the spring of 1981 a new organisation was set up by young people to combat racism in the town - the Luton Youth Movement. Partly this arose out of a sense of frustration with the seemingly endless intrigues within the local Labour Party, Community Relations Council and traditional community groups, none of which had proved capable of organising effective action against racist attacks

The inspiration was clearly the militant Asian youth movements that had developed elsewhere in the country from 1976 onwards, notably in Southall and Bradford, to defend communities from attack. Asian young people were a key driving force in setting up Luton Youth Movement, but from the start it also had African Caribbean and white members. I'm not not sure that this was making a particular political point about the politics of black autonomy so much as reflecting the fact that it initially grew out of a mixed friendship group in a small town where allies were thin on the ground. The LYM aims included 'To protect our communities from racial attacks (including police harassment)' and 'To fight immigration controls and racist laws'. The latter point was important as during 1981 a new Nationality Act was going through Parliament imposing further restrictions on immigration. Its effects were seen later when, in January 1983, Luton Pakistan and Kashmir Welfare Society complained that Scotland Yard and local police had raided 60 houses in Luton, with 200 people being questioned at Luton police station in an alleged search for forged passports.

Self defence

The Luton Youth Movement saw organising community self-defence against racist attacks as a key task. A sympathetic article in the local Evening Post at the beginning of July 1981 reported: 'People who live in fear of racial attacks are being successfully protected by a group of young people in Luton'. Mohammed Ikram, 19, the chair of LYM was interviewed and gave a picture of its activities: "It's going very well. We move in with victims to make sure the attackers do not try again. The police have not proved efficient enough. We are prepared to meet force with force if necessary'. The defence work was said to involve young people aged 14 to 24 working three hour shifts, with a team of six people inside the house being protected and six more outside ('Protected by Youngsters', Evening Post, 3.7.81).

In July, the LYM announced plans to set up an emergency telephone system to help people under threat of racist attack. The idea was to mobilise people at short notice to respond to calls to a publicised telephone number. The Luton News reported that 'They decided to set up the defence network after hearing that an Asian family fled from their Luton council house after having excreta and a threatening letter pushed through their letter box' (Luton News, 16.7.81).

|

| My LYM membership card |

The Luton Youth Movement March

"In Luton last Boxing Day [December 1980] the Mosque in Westbourne Road was attacked by a group of around 200 racists. Recently, car loads of young racist thugs have been intimidating school students at many of the local schools, there have been numerous other attacks in this area. People can no longer live their lives without the fear of racist abuse and intimidation" (Luton Youth Movement leaflet, May 1981)

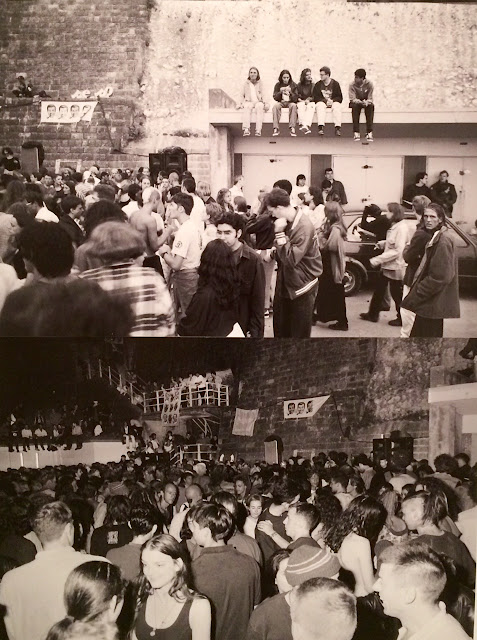

On Saturday 16th May 1981 the Luton Youth Movement 'march against racist attacks' took place. About 50 people set off from Kingsway Park in Dunstable Road shortly after noon behind banners saying 'Luton Youth Movement' and 'Black and White Unite and Fight'. Other banners included Luton Socialist Workers Party and Anti-Nazi League.

More joined along the way, including when the march stopped at the Mosque. By the time the march finished with a rally by the Town Hall around 'numbers had swollen to 200, mostly Asian people’ (Herald) to hear speakers from Brixton and Southall as well as local people such as Akbar Khan from the Pakistani Welfare Association.

As the meeting was coming to an end it was charged by about 30 racist skinheads giving Nazi salutes and shouting Sieg Heil. The marchers counter charged and fist fights broke out before the police escorted the racists away. One LYM supporter was quoted in the Luton News as saying: "The word went round that the fascists were out. Other young people surged from the Arndale Centre to help us. There were a few moments when I thought it was going to explode like Brixton. If the police had drawn their truncheons I think it would have done".

|

"Fascist skinheads brought violence to Luton on Saturday when they attacked a multi-racial meeting outside the Town Hall". There is a very blurry image of me in that top photo! (Luton News 22 May 1981)

|

Less than an hour later, the same group were involved in a racist attack less than a mile away. An Asian woman and two children in Pomfret Avenue were 'surrounded by about 30 skinheads chanting racist and Nazi slogans' (Luton News).

That evening there was further trouble at a punk gig at the Bunyan Centre in Bedford. Skinheads stormed the stage while Luton punk band UK Decay were playing. Lead singer Abbo later recalled: 'We'd only played a couple of songs and I remember being pushed off the stage by a bonehead after I said some anti racist comment in reply to their seig heiling/racism chants, and within a minute it seemed the venue was empty aside from the band , crew and heeps of skinheads , the fights seemed to go on forever until the police arrived , and then they got a hiding from the skinheads'. Seven skinheads were later jailed for this. Although Bedford is some miles from Luton, there were strong cross-county connections within different musical and political sub-cultures. It seems very likely that at least some of those involved in attacking the LYM rally were also present at the UK Decay gig.

The following day a man received facial injuries when he was attacked by three men near Luton Town Football ground after he went to the aid of an Asian youth being beaten up, and there were further racist attacks in the following weeks. On June 13 a group of youths ran on to a cricket pitch and abused and attacked Pakistani players at the Blue Circle Cement Sports Ground, Houghton. They shouted racist insults and made threats, mentioning the National Front (Luton News/Dunstable Gazette, 10.12.1981). A week later the Carnival Queen at the Marsh Farm Festival had a police guard after threatening racist telephone calls to organisers. Bijal Ruparelia, 16, of Indian-Kenyan descent, had to ride in a closed car rather than the usual open-top vehicle in the carnival procession because of threats that she would be stoned. The Carnival passed off without incident (Luton News, 25.6.1981).

All of this was leading up to the full scale riot that occurred in the town in July 1981 as part of the wave of urban uprisings that swept across the country, a riot that in Luton was sparked by the presence of racist skinheads once again in the town centre. That's a story I will return to in another post.

Other Luton writings:

|

| 'Skinheads making Nazi salutes threatened anti-racist marchers' (Herald, 21 May 1981) |

|

| "Teenagers fight racism" (Evening Post, 18 May 1981) |

|

| Luton Leader, May 1981 |

|

| Luton SWP leaflet from the demo. I was a member around this time, the local branch was youthful and combative and were always on the frontline whatever criticisms I was to have of their politics as I ran away with the anarchists later on! The leaflet refers to meetings at the International Centre in Old Bedford Road, a venue for a number of radical meetings in this period including the Luton Youth Movement and Irish solidarity events (the Irish Hunger strike was underway at this time, with Bobby Sands and Raymond McCreesh dying in the two weeks before the LYM march). The leaflet mentions an unemployed march due to come through Luton on 25th May 1981 - this was the People's March for Jobs which features briefly in the opening credits to 'Blinded by the Light'. |

'Luton Racist Attacks': A report on racist attacks in Bury Park area from Fight Racism ! Fight Imperialism! (Revolutionary Communist Group paper), July/August 1980. This describes a racist attack in November 1979 on the Shalimar restaurant and an attack by 60 racist skinheads on Asian people outside the local cinema (the Ocean). In the latter case local youth fought back, and 15 were arrested. Then in Feburary 1980 'Over 20 Asian shop windows were smashed in one week.... by thugs on motorbikes'

Neil Transpontine (2019), Blinded by the Light - memories of 1980s Luton racism and job cuts <https://history-is-made-at-night.blogspot.com/2019/08/blinded-by-light-and-memories-of-1980s.htmll>. Published under Creative Commons License BY-NC 4.0. You may share and adapt for non-commercial use provided that you credit the author and source, and notify the author.