|

|

| Counter Information, July 1987 |

|

| Workers Press, 14 March 1987 |

|

| Workers Press, 21 March 1987 |

|

|

| Counter Information, July 1987 |

|

| Workers Press, 14 March 1987 |

|

| Workers Press, 21 March 1987 |

|

| 'it highlights optimism and transformative moments that can alter society' |

.jpg) |

| 'The rave beckons and the moon shines... A portal brimming with promise. A labyrinth of sound. And in between each laser beam WE is found' (Alicia Charles) |

|

| Original cassette pack from Urban Shakedown with Randall, Bryan Gee etc. |

Long ago and far away (well mid 1980s Luton) there was a great punk band called Karma Sutra. I hung out with them and made a few squiggly noises on my wasp synth on one of their 1985 demo tapes. Now 35 years later said demo tape and others from that time have appeared on vinyl as an album 'Be Cruel With Your Past And All Who Seek To Keep You There' put out by Sealed Records (listen/buy it here). It comes with a great booklet with interviews and flyers. For me Karma Sutra were a portal into anarcho-punk and its associated activism, perhaps in particular hunt sabbing as I explain in the following

I’d had the Crass records, the Conflict badges, and a mohican, I’d been on a Stop the City demo too but my real initiation into the world of ‘anarcho punk activism’ didn’t come until September 1st 1984 when I went to a Hunt Saboteurs benefit gig at Luton library theatre arranged by local band Karma Sutra. Headliners Antisect from Northampton were one of the more metal tinged punk outfits, with heavy guitar riffs and gruff vocals growling “why must I die?” (The “I” in question being a laboratory animal of course).

If the extremism of noise and content was impressive it wasn’t unexpected. What really amazed me was what was going on off the stage. I’d been to loads of gigs where I’d steamed in with my mates, bought some drinks, watched the bands, and left with the only interaction with others being some slam dancing at the front. Here there were people talking, and busy bookstalls from the Hunt Saboteurs and from Housman’s, the London radical bookshop, with a selection of anarchist papers and other publications (I later found out that several people from the Luton scene were working the odd shift there, and eventually I did the same myself).

I chatted with someone about hunt sabbing and within a week I was standing in a field in Northamptonshire at 8 am in the morning at the beginning of the fox cub hunting season. It was the start of a couple of years of intense activity, with countless hours spent in the back of a white van hurtling between punk gigs, hunts, demonstrations and protests. I'd been politically involved in various left wing movements before but this was a different intensity of activism.

Of course these were tumultuous times across the world – the days of Thatcher vs. the miners, of Reagan and the new Cold War, of uprisings against Apartheid in South Africa. And in towns and cities across the UK, some of the most determined opposition to the state of the world came from groups of young, invariably black-clad punks. This article is a snapshot of one of those scenes, in Luton, but similar stories could be told about many other places.

Punk in Luton

Thirty miles north of London, Luton in the mid-1980s was still an industrial town dominated by the Vauxhall car factory, as it was to remain until General Motors stopped making cars there in 2002. There had been a punk scene in the area since the early days: The Damned played one of their first gigs at Luton’s Royal Hotel in 1976 and the Sex Pistols played at the Queensway Hall in neighbouring Dunstable in the same year. Luton’s first punk band, The Jets, featured on the famous Live at the Roxy album in ’77.

The best known punk band to come from Luton was UK Decay, formed in 1979. The band had some association with Crass - in December 1979 they played with Crass and Poison Girls at a gig in a tin Nissan hut at Marsh Farm in Luton, and their final record – the ‘Rising from the Dread’ EP - was released on Crass’s Corpus Christi label in 1982. But while UK Decay released the great anti-war track ‘For my country’, they weren’t really part of that anarcho-punk protest scene as such. Along with Northampton’s Bauhaus they were developing a proto-goth aesthetic, referencing horror themes and plundering Edgar Allen Poe and Herman Hesse for inspiration. Indeed the reference to them as ‘the face of punk gothique’ by Steve Keaton in Sounds (February 1981) is credited as being one of the originators of the term ‘goth’ for this emerging sound.

UK Decay were influential stalwarts of the indie charts, and among other things supported The Dead Kennedys on their 1980 UK tour. For a while they were involved in a short lived punk/new wave record shop in Luton town centre, Matrix, which closed down shortly after a party where the Kennedys and other party goers ran amok in the Arndale Centre car park.

By 1984 UK Decay had split up, giving rise to a couple of splinter bands (Furyo and In Excelsis) and the post-punk scene too had begun to fragment. The town’s sub-cultural outcasts tended to congregate at one pub in particular - The Blockers Arms in High Town Road (of which more here). Among the punky types there were different factions, albeit overlapping and coexisting peacefully – some slightly older first generation punks, early goths, what would later be called indie kids, and what might be termed ‘anarcho-punks’.

There were no strict borders between these groups - every individual had their own combination of politics, music tastes and hairstyles - so it’s perhaps misleading to talk of a discrete, separate anarcho-punk scene. But within this continuum there was a definite current that was more overtly political and musically more into the bands like Crass and Conflict.

I don’t think most people like this would have defined themselves then as anarcho-punks or even necessarily as anarchists, but there was a shared, loose anti-authoritarian politics, with a strong focus on being against war and militarism and for animal rights. People were typically vegan at a time when supermarkets barely catered for vegetarians - these were the days of homemade houmous.

It would be misleading too to use the term ‘Crass punks’. Crass had certainly been very influential earlier on but they were coming to the end of their active life, playing their final gig in 1984 – a miners’ benefit in Aberdare. At the thrashier end of things Conflict were now the most influential band, but the scene had become much more musically diverse. Bands like Chumbawamba with their harmonies, Slave Dance with their situationist squat funk sound, and No Defences with their tricky time signatures were a long way from being Crass or Conflict copyists.

|

| Karma Sutra |

|

| Karma Sutra image from UK Decay communities website |

In Luton, the house band of the scene was Karma Sutra. They had been included on Conflict’s 1984 Mortarhate compilation ‘Who? What? Why? When? Where?’ with their track ‘It’s our World Too’ and were later to release an album ‘The Day Dreams of a Production Line Worker’ on their own Paradoxical Records. Another Luton band on a similar wavelength, Dominant Patri, had already split up by 1984. The other main ‘anarcho’ band in the town at the time was Penumbra Sigh, who formed I believe in 1985, and there were also like-minded bands in nearby towns, such as Medical Melodies in St Albans.

I sometimes operated the slide projector at gigs for Karma, and I occasionally turned up at their rehearsal space with my wasp synth – you can hear it on one of their demo tapes from the period recorded in Luton's Midland Road studio. But mostly I just travelled around with them and others to gigs – squat gigs in London such as in the Ambulance Station on the Old Kent Road, a pub in Brixton or a bus station by Kings Cross; gigs in far off places like a CND benefit supporting Chumbawamba in Stockport, gigs in nearby towns like Welwyn Garden City and St Albans; gigs with Conflict, Chumba, Antisect, The Sears, Blyth Power, Flowers in the Dustbin, Slave Dance, State Hate, No Defences, Sacrilege, Brigandage, Black Mass, The McTells, The Astronauts and many more. But the music was only part of it and here I want to focus on some of the other things we got up to.

|

| Chumbawamba, Karma Sutra and Sacrilege, CND benefit at Scunthorpe Baths, 1 March 1985 (I remember burning my hand on the slide projector as well as some great music!) |

Hunt Sabbing

‘It’s normally a

quiet Northamptonshire lane – but on this occasion it looks more like a

battlefield. Furious members of the Grafton Hunt are blocking the road with

their horses and refusing to move. Angry hunt saboteurs rev their cars, hoot

their horns and demand that the horses get out of the way… A battered van and

an assortment of old cars appeared and about 30 mainly young protestors dashed

down a track close to the wood. A genuine Cotswold hunting horn, blown by a

saboteur, did a good impression of the Grafton’s rallying horn, while the rest

of the party joined in with fake shouts and calls…There’s another whirling

confrontation and a young female saboteur is lying unconscious in a ploughed

field – knocked flat by a horse… another saboteur is thrown into a stream by

hunt followers, and there are more scuffles’ (When the hunters become the

hunted’, Alex Dawson, Chronicle and Echo, September 10 1984)

The fine art of preventing hunters killing foxes and other animals dated back to the formation of the Hunt Saboteurs Association in 1963. Luton had been home to a particularly militant sabbing group in the early 1970s, from which emerged the Band of Mercy to take direct action including sabotaging hunt vehicles. This group, which included Ronnie Lee, was to become one of the founding cells of the Animal Liberation Front.

The mid-1980s Luton sabs operated across the Beds, Bucks, Herts and Northants countryside with occasional forays further afield. Our nearest fox hunt was the Enfield Chace, in pursuit of which we would head out of town having scoured Horse and House magazine for intelligence of where they were to be found of a Saturday morning.

We quite often went out with the Northampton group, sabbing the Pytchley, Grafton or the Vale of Aylesbury fox hunts.. There was also a group in Bedford but even though there were some sound people in it we didn’t entirely trust them because we suspected that their van driver had dubious fascist connections (she later ended up as a Labour councillor in Milton Keynes, I guess people can change).

The biggest events were national and regional ‘hits’, when sab groups from across a wide area would converge on one hunt. Sometimes these would feature spectacular clashes, with red coated hunters on horseback, hunt followers, police and a hundred or more brightly haired sabs scuffling and chasing each other, and sometimes a fox, across fields and through woods. I remember being in the woods near Sole Street in Kent, disrupting the East Kent hunt with sabs from Canterbury, Thanet, Brighton and Surrey in March 1985. It felt like being in a medieval peasants revolt with sabs carrying sticks charging at the hunters deep in the trees - it was the week that Kent miners returned to work at the end of their strike and class war was in the air.

Ideally the hunt would be delayed by stopping it moving off, or blockading the kennels where the hounds were kept. At the start of the 1985 season for instance, around 100 sabs blockaded the kennels of the Cambridgeshire Foxhounds, preventing the van carrying the hounds from leaving on time [I believe the pictures below are from that day, I recognise a couple of Coventry sabs in them including all in black John Curtin].

|

| The guy on the right rode his horse straight at me, so I was knocked on the ground a couple of seconds after taking this photo! |

At other times, sometimes with as much effect, it would just be a handful of us, hardly seeing the hunters but distracting the hounds from a distance blowing hunting horns or spraying anti-mate on the ground to obscure the scent of the fox.

There were also less direct tactics - there were tales of some sabs doing magic rituals to protect the fox before setting out on a Saturday morning. This was the first time I had heard of such 'magical activism' and shortly afterwards I was introduced to the work of Starhawk - hanging around court while watching one of the Unilever trials (arising from a mass animal liberation league raid on a Bedfordshire laboratory) someone was reading 'Dreaming the Dark: Magic, sex and politics' which described the work of witches in the US peace and anti-nuclear movements.

Whatever the numbers out sabbing the conflict was usually uneven with the hunting cavalry facing the animal rights infantry. On my very first hunt, a sab was knocked out by a horse from the Grafton Hunt near Slapton in Northants. On another occasion I was knocked flying by a horse, but escaped serious injury. A few years later, in 1991, hunt saboteur Mike Hill was to be killed by a hunt vehicle used by the Cheshire Beagles. In 1993 15 year old Tom Worby was killed when he was dragged under the wheels of the Cambridgeshire's houndvan (and indeed in 1995 Jill Phipps, who I remember meeting at that first hunt at Slapton, was killed by a lorry during an animal rights protest at Coventry airport).

|

| My first time hunt sabbing - a woman lies injured after being hit by a horse from the Grafton Hunt. Her friend comforts her - note Crass patch on trousers (Chronicle and Echo, September 10 1984). |

The police generally turned a blind eye to any violence inflicted by hunt followers on sabs, and it was the latter who tended to get arrested if there were any clashes. For instance in March ’85, eleven sabs were arrested as we tried to stop the Old Berkeley Beagles hunting hares near Thame in Oxfordshire.

Sometimes the hunt could not be found at all, and there would be fruitless tours of country lanes in the back of a van. Where large numbers of sabs were gathered together with nothing to do the temptation to mischief elsewhere was strong. In March 1986, a big group of sabs who had originally gathered to oppose the Warwickshire hunt headed to Leamington Spa town centre. After a sit down in McDonalds, we moved to a couple of local fur shops, The Sunday Mercury reported (16.3.1986): ‘A crowd of 70 demonstrators caused disturbances throughout the afternoon in the centre of Leamington. Some burst into Brians Specialist Furriers in Regent Street and grabbed expensive fur coats from racks before hurling them outside into the road’. 12 people were arrested including three women from Luton who were detained over the weekend - one of whom was slapped in the face by police for refusing to answer questions. A ‘Leamington Dirty Dozen Defence Fund’ was set up to support them.

|

| Report of Leamington Spa animal rights protest from Luton Animal Rights bulletin no.2, April 1986- one person was later jailed for 6 weeks for assault |

On another occasion, in November 1986, Luton sabs headed off for a national hit near Leicester with around 150 sabs from Coventry, Leamington, Birmingham, Sheffield, Northampton, Rugby, Leicester and Lincoln. After chasing after the hunt, aided by CB radios, fog stopped play and the hunt went home early without a kill. The sabs headed into Leicester to join an anti-fur demo, with one of the Luton group being arrested for ABH after a scuffle during a sit in at a fur shop.

Not all sabs were punks of course, but our group was predominantly so, as were others. As well as the sabbing itself, keeping it going involved raising funds for van hire, petrol, materials and the occasional fine. Jumble sales and benefit gigs were the main source of income, including an amazing hunt sabs benefit we put on back at the Luton Library Theatre in 1985 with Chumbawamba, No Defences and Karma Sutra. Karma also played a benefit gig for the Leamington defendants at Luton’s Cock Inn (May 1986) along with Medical Melodies, Herb Garden and Kul.

|

| 1985 Luton Hunt Sabs benefit with Chumba, No Defences, Karma Sutra and Penumbra Sigh. What a great gig that was, No Defences' mesmerising performance was fortunately recorded for posterity |

|

| Luton hunt sabs jumble sale 1986 |

|

| The donkey-jacketed Luton Hunt Sabs march through the mud near Pulloxhill in Bedfordshire, January 1985. I think this may be the day described in diary extract below |

[This is an edited extract, with newly added pictures, from my article - Neil Transpontine, Hyper-active as the day is long: anarcho-punk activism in an English town, 1984-86 in 'And all around was darkness' edited by Gregory Bull and Mike Dines, Itchy Monkey Press, 2017. The full article goes on to look at more Luton activism covering animal rights, anti-apartheid, the peace movement, Stop the City, the miners strike and more. The book is an excellent collection of participant accounts of the scene including The Mob, Crass, Flowers in the Dustbin, anarcho-feminism and Greenham Common etc. You can buy copies of it here and recommend you do if you are at all interested in this kind of stuff. You can also download a copy from Hitsville UK]

|

| Red Action, April 1985 |

|

| Report of 1991 demonstration - Troops Out, March 1991 |

|

| 1993 flyer for march called by Bloody Sunday March Organising Committee (Troops Out Movement, Irish in Britain Representation Group, Women & Ireland Network, Black Action and the Wolfe Tone Society) |

|

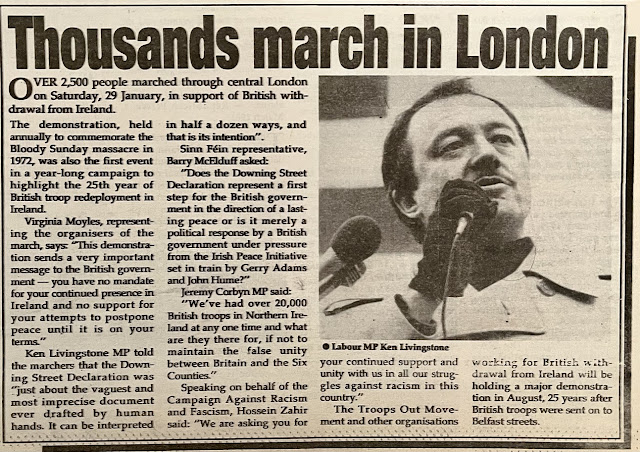

| Report from Troops Out, March 1993. Speakers on 1993 London Bloody Sunday demo included Jim Kelly of the Casement Accused Relatives Committeee, Unmesh Desai (Campaign Against Racism and Fascism), Ken Livingstone MP, Mick Conlon (Sinn Fein) and Gerry Duddy whose 17 year old brother Jack was shot dead on Bloody Sunday |

|

| 1994 demo leaflet |

|

| The 1994 London Bloody Sunday demonstration |

|

| Report of 1994 demo with speakers including Ken Livingstone MP, Jeremy Corbyn MP and Hossein Zahir of Campaign Against Racism and Fascism (from An Phoblact, 4 February 1991) |

| ||

1998 London demo flyer

Martin McGuinness speaks in London on 1998 Bloody Sunday demo |

|

| 'Justice for the Casement Accused' banner in Manchester - an infamous miscarriage of justice case in Belfast. |

|

|

| Relatives lead the 1992 Derry march |